1. The Warren Commission Botched the Kennedy Autopsy

2. Warren Commission One-Bullet Theory Exploded

For the first time, a man who really knows what he's

talking about analyzes the gunshots that killed the President.

FOR

the past three years, whenever Dr. Milton Helpern has discussed the

subject of bullet wounds in the body, he has been asked for his opinion

on President Kennedy's assassination.

Those who are knowledgeable

about the subject of bullet wounds listen to what he has to say with a

respect that borders on reverence. As Chief Medical Examiner of the

City of New York, he has either performed or supervised approximately

60,000 autopsies; and 10,000 of these have involved gunshot wounds in

the body. The New York Times has said that "he

knows more about violent death than anyone else in the world."

No

one can come close to matching his vast experience with bullet wounds.

Dr. Helpern's book, "Legal Medicine, Pathology and Toxicology," was

cited as the standard reference work on the subject by Lieutenant

Colonel Pierre Finck, one of the doctors who assisted in the autopsy on

President Kennedy's body, in his testimony before the Warren Commission.

It

now seems incredible that Dr. Helpern's opinion was not one of the

first sought when the official investigation into the President's death

was launched. It has not yet been asked for, either officially or

unofficially, by anyone connected with the Warren Commission.

"The

Warren Commission," Dr. Helpern says, shaking his head sadly, "was a

tragedy of missed opportunities for forensic medicine. Its entire

approach to the problems of the President's wounds shows a total lack

of familiarity with the subject. The Warren Commission had an

opportunity to settle, once and for all, a great many of the confusing

doubts, but because none of its members or its legal staff had any

training or knowledge in forensic medicine, those opportunities fell by

the wayside. It is tragic! Really tragic!"

Almost

every week, Dr. Helpern plays host to some official visitor from a

foreign country whose specialty is forensic medicine, and invariably

the subject of the assassination comes up.

"I am continually

amazed," he says, "at the refusal of the Europeans to accept the

conclusions of the Warren Commission as being fact. Millions of

Europeans apparently still feel strongly that the Commission report was

nothing but a whitewash of some kind to cover up a vicious conspiracy.

My friends in forensic medicine who have read the report in detail -

and it seems that most of them have - simply cannot believe that the

examination and evaluation of the President's bullet wounds could have

been handled in the manner which the report describes.

"I am

talking now only about the medical evaluation of the bullet wounds

themselves, nothing else. The FBI certainly did a commendable job on

the other phases of the case, but the FBI had to rely entirely on the

medical information furnished it by the three doctors who performed the

autopsy. The FBI does not have its own experts in forensic medicine.

There is no reason for them to have. The FBI undoubtedly has had more

experience with firearms identification - that is, matching a

particular bullet to a particular gun - than any other agency in the

world; but the FBI is seldom called upon to investigate a murder.

Murder is a crime which usually involves a state jurisdiction only.

Bullet wounds in the body are not the FBI's long suit."

[EDITOR'S

NOTE: And so is death by poisoning. In April, Dr. Helpern won a

toe-to-toe confrontation with the nation's top criminal lawyer, F. Lee

Bailey, when Dr. Carl A. Coppolino was convicted in Naples, Florida, of

murdering his wife, Carmela. Dr. Helpern and his assistants convinced a

jury that Dr. Coppolino had injected a lethal dose of succinylcholine

chloride, a muscle-relaxing drug, into Carmela's left buttock. The

result was death by suffocation.

Bailey's effort to counter the testimony of Dr. Helpern

and his assistants with experts of his own proved futile.]

Even

allowing for the vagaries of individual bullet wounds, it has been

possible to formulate some general principles which permit the experienced

forensic pathologist to be reasonably accurate in his calculations.

Regardless of the number or position of the bullet wounds in the body

in a given case, the first step is to determine whether each wound is a

wound of entrance or a wound of exit.

When a bullet strikes the

skin, it first produces a simple indentation, because the skin is both

tough and elastic, and the tissues underneath are not rigid and

resistant. This stretches the skin immediately under the nose of the

bullet. The bullet, which is rotating as well as moving forward, is

definitely slowed up at this point of first contact, but it then more

or less bores its way through the skin and the tissues underneath, and

courses on into the body. The skin is stretched by the bullet at the

point at which it passes through; it then returns to its former

condition, so that the size of the wound of entrance appears to be

smaller than the diameter of the bullet which made it. Usually, there

is only a small amount of bleeding from wounds of entrance, since

tissue destruction at this point is not great. These rules apply to

bullet wounds that are the result of the gun being fired at distances

in excess of twenty-four inches. A different set of rules applies when

the gun is held in direct contact with the skin or is fired from a

distance less than twenty-four inches.

Wounds of exit, on the

other hand, are usually larger than the bullet, since the bullet tends

to pack tissues in front of it. These wounds are ragged, torn, and

sometimes have shreds of fat or other internal tissues extruding from

them. As a result, wounds of exit may bleed far more extensively than

wounds of entrance. This, however, is not invariably the case.

"You

always are guided by the general rules that apply to bullet wounds."

Dr. Helpern says, "but you must also be on guard for the bizarre, the

unusual, the once-in-a-million case, the wounds that, to the novice,

seem to defy physical laws. It is not a job for the beginner or the man

whose knowledge is limited to a lecture or two, or to what he has read

in some article or textbook."

To fully appreciate the gravity of

Dr. Helpern's observations on the medical facts of President Kennedy's

death, it is necessary to go back to the historic day of Friday,

November 22, 1963.

Sometime between twelve-thirty p.m., when the tragedy

struck in Dallas, and the arrival of Air Force One

at Andrews Air Force Base just outside of Washington at

five-fifty-eight p.m., Mrs. Kennedy decided that the autopsy on her

husband's body should be performed at the Naval Medical School in

Bethesda, Maryland. She was given two choices: either the Army's Walter

Reed Hospital or Bethesda. She selected the Naval Medical School

because of the President's World War II service in the Navy.

Certainly,

Mrs. Kennedy could not be expected to have any knowledge of forensic

medicine; and in her hour and the nation's hour of shock and

bereavement, she made a logical choice. The point that disturbs Dr.

Helpern, however, is the fact that the choice was left to her. It was

not only an unpleasant, additional personal burden which should have

been spared her, but it indicates as well the total lack of

understanding of the subject of forensic medicine.

"It shows," he

says, "that we are still laboring under the delusion that an autopsy is

a computerized, mathematical type of procedure, and that any

doctor is capable of performing it, especially if he is a pathologist.

If he can run a correct urinalysis, ergo this automatically qualifies

him as an expert on bullet wounds in the body.

There can be no

doubt but that this fallacious assumption was the real spawning ground

for the contagious rash of anti-Warren Commission books that have

poured out during the past three years. Their genesis can be traced

directly to what was done and not done in a single operating room in

the Naval Medical School in the evening hours of Friday, November 22,

1963.

The autopsy was performed by Commander James J. Humes,

assisted by Commander J. Thornton Boswell and Lieutenant Colonel Pierre

Finck.

In testimony before the Warren Commission, Commander

Humes, director of the Naval Medical School at the Navy Medical Center

at Bethesda, established himself as a qualified pathologist. He

admitted, though, that his practice had been "more extensive in the

field of natural disease than violence."

In short, the author says, "Humes was a 'hospital'

pathologist, rather than a forensic or medico-legal pathologist."

The

hospital pathologist performs his autopsies on cases where death occurs

in a hospital, usually as a result of some disease and where the cause

of death can be presumed. It is generally performed to confirm a

diagnosis.

A forensic pathologist, on the other hand, performs

autopsies usually where death is not attended by a physician. In these

cases, a pathologist often follows misleading, frustrating clues. His

work is much trickier, since cause of death is often crucial to

subsequent legal action.

"The 'hospital' pathologist," the author

says, "is as much out of his field when he attempts a medico-legal

autopsy as is the chest surgeon who attempts a delicate brain

operation."

The Warren Commission did not attempt to establish

the expertise of Commander Boswell in gunshot wounds, the author says,

because "he had absolutely none worthy of mention." Commander Boswell

was chief of pathology at the Naval Medical School.

Colonel

Finck, who was then chief of the Wound Ballistics Pathology branch of

the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, told the Warren Commission

that he had personally performed about 200 autopsies for the Army in

Frankfurt, Germany, while serving there from 1955 to 1958. In his

current capacity, he said, he had personally reviewed 400 autopsies.

But

he was vague on the number of bullet-wound cases in his 200 personally

performed autopsies, except to say that there were "many." Moreover,

the fact that he reviewed 400 cases did not mean that he "presided at

the autopsy table and attempted a personal evaluation of whether a

bullet wound...is a wound of entrance or a wound of exit."

The

author says that Colonel Finck was perhaps the most qualified of the

three who performed the autopsy on the President, but adds that his

experience was mostly "supervisory and administrative."

The men

were accomplished in their respective fields of general pathology, the

author sadly concludes, but their field "was not bullet wounds in the

body."

One of the key aspects of the autopsy was to determine

whether the front neck wound was one of entrance or exit. If it was an

entry wound, then a second assassin was indicated.

Unfortunately,

this was difficult to determine, since Dr. Malcolm O. Perry had

performed a tracheotomy at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas in a

futile attempt to save the President's life, thus obscuring the neck

wound. At no time in Dallas was the body turned over to look for a

corresponding wound in the back, and therefore the front neck wound was

assumed to be an entrance wound.

The difficulties encountered by

the autopsy surgeons were compounded by the fact that Commander Humes

first talked to Dr. Perry the morning after the autopsy, when the body

was already resting in the White House. Thus they had worked under the

assumption that there were only three bullet wounds - the two in the

head and the one in the back of the neck, since they attributed the one

in the front of the neck to the tracheotomy.

They thus assumed,

in their "inexperienced efforts" to probe the neck wound, that a third

bullet had been found on a stretcher at Parkland, they abandoned their

search.

In testimony before the Warren Commission, Commander

Humes expressed no doubt that the wound in the throat was a wound of

exit - even though the only ones who saw the original wound were the

doctors in Dallas. And this was before they made the tracheotomy that

extended the wound.

In other testimony, both Dr. Perry and Dr.

Charles S. Carrico, resident surgeon at Parkland, said they could not

determine whether the wound was one of entrance or exit. "It could have

been either," Dr. Carrico said.

This was the testimony that

satisfied the Commission and permitted it to conclude that "the

findings of the doctors who conducted the autopsy were consistent with

the observations of the doctors who treated the President at Parkland

Hospital."

"The tragic, tragic thing," Dr. Halpern explains in

summarizing his comments on the medico-legal aspects of President

Kennedy's death, "is that a relatively simple case was horribly botched

up from the very beginning; and then the errors were compounded at

almost every other step along the way. Here is a historic event that

will be discussed and written about for the next century, and gnawing

doubts will remain in many minds, no matter what is done or said to

dispel them."

What were these step-by-step errors?

"I've

already touched on the gravest of them all - the selection of a

'hospital' pathologist to perform a medico-legal autopsy. This stemmed

from the mistaken belief that because a man can supervise a laboratory

or perform a hospital autopsy to see whether a patient died from

emphysema or heart disease, he is qualified to evaluate gunshot wounds

to the body. It's like sending a seven-year-old boy who has taken three

lessons on the violin over to the New York Philharmonic and expecting

him to perform a Tchaikovsky symphony. He knows how to hold the violin

and bow, but he has a long way to go before he can make music."

Does this observation apply to Lieutenant Colonel Pierre

Finck?

"Colonel

Finck's position throughout the entire proceeding was extremely

uncomfortable. If it had not been for him, the autopsy would not have

been handled as well as it was; but he was in the role of the poor

bastard Army child foisted into the Navy family reunion. He was the

only one of the three doctors with any experience

with bullet

wounds; but you have to remember that his experience was limited

primarily to 'reviewing' files, pictures and records of finished cases.

There's a world of difference between standing at the autopsy table and

trying to decide whether a hole in the body is a wound of entrance or a

wound of exit, and in reviewing another man's work at some later date

in the relaxed, academic atmosphere of a private office. I know,

because I've sweated out too many of these cases during the past

thirty-five years. Colonel Finck is extremely able in the type of

administrative work which has been assigned him over the years."

Are

there any crucial steps that should have been taken that were omitted

that Friday evening in the autopsy room at the Naval Medical School?

"The

major problem in any gunshot case, of course, is to determine which is

the wound of entry and which the wound of exit. This is basic. All the

so-called critics of the Warren Commission Report would be left

dangling in mid-air with their mouths gaping unless they can suggest or

argue that the hole in the front of the President's throat was a wound

of entrance. Deprive them of this opportunity for speculation and you

pull the rug right out from under them. Give it to them - and they now

have it - and they can bring in all kinds of unreliable eyewitness

reports of shots coming from the bridge across the underpass, or from

behind the screen of trees in Dealey Plaza, and puffs of blue smoke

that remained suspended in the air with police officers scrambling up

the bank to investigate these illusory puffs of smoke. Smoke from

gunshots just doesn't behave like that."

Specifically, how could

a positive determination have been made at the time of the autopsy that

the throat wound was a wound of exit or a wound of entrance?

"In

a great many cases, the only safe way to reach a conclusive decision is

to compare the size and characteristics of each wound on the end of the

wound track. It's easy for textbook writers and their readers to assert

pontifically that the wound of exit is always

larger than the wound of entrance, and the wound of exit is ragged

whereas the wound of entry is smooth, so that you have no difficulty in

taking a gross, eyeball look and saying, 'this is the entry wound' or

'that is the exit wound.' This isn't true at all. The

difference

between the entry wound and the exit wound is frequently a lot more

subtle than that. Many of the wounds require careful and

painstaking study before you can reach a decision."

But wasn't

the throat wound gone at the time of the autopsy? In one

place,

the Warren Commission Report states: "At that time they [the autopsy

surgeons] did not know that there had been a bullet hole in the front

of the President's neck when he arrived at Parkland Hospital because

the tracheotomy incision had completely eliminated that evidence."

At another point, the report says: "...since the exit wound

was

obliterated by the tracheotomy."

"No, you see, the staff members

who wrote that portion of the report simply did not understand their

medical procedures; and they did not know enough to seek medical

guidance. Here's what the autopsy protocol says about this

throat

wound; '...it was extended as a tracheotomy incision and thus its

character is distorted at the time of autopsy.' The key word

here

is extended.

That

bullet wound was not 'eliminated' or 'obliterated' at all.

What

Dr. Perry did was to take his scalpel and cut a clean slit away from

the wound. He didn't excise it or cut away any huge amount

of

tissue, as the report writer would have you believe."

What about the description in the autopsy protocol that

"its character is distorted"?

"Certainly, its character is distorted in the sense that

the original wound was extended

in length by Dr. Perry's scalpel; but this throat wound could still

have been evaluated. Its edges should have been carefully put

back together and restored to their original relationships as nearly as

possible. It should have then been studied and finally

photographed. By comparing this throat wound with the wound

in

the back of the neck, there should have been no room for doubt as to

which wound was of entry and which of exit. This would

automatically establish the course of the bullet, whether from front to

back, or back to front."

Why wasn't this procedure followed?

"I

can't crawl into the minds of the surgeons and answer for them.

I

can only offer my own speculative opinion. In the first

place,

their lack of experience deprived them of the knowledge of what should

have been done. Secondly, it appears from every facet of the

evidence now available that at the time they finished their autopsy and

closed the body so that it could be prepared for burial, they labored

under the illusion that the hole in the back of the neck was both a

wound of entrance and a wound of exit. They thought the

throat

wound was nothing more than a surgical wound, so there was no need to

pay it any special attention."

Are there any other procedures

followed by the autopsy surgeons that have furnished ammunition to the

critics of the Warren Commission Report?

"Unfortunately, there

are. The phrasceology in the formal autopsy protocol itself

implies or suggests that the doctors still harbored doubts and

uncertainties at the time it was written. In speaking of the

neck

wounds, the protocol describes them as 'presumably of entry' and

'presumably of exit.' It says: 'As far as can be ascertained,

this missile struck no bony structure in its path through the body.'

Well, that just doesn't read like the work of men in

confident

command of their ship.

"On the other side of the coin, the

writers of the Warren Commission Report went to the opposite extreme

when they tried to force unanimity of opinion on all the doctors at

Parkland Hospital in support of the autopsy surgeons that the throat

wound had to be a wound of exit. When you put too much

tension on

the evidence, by pulling and tugging on it, in an effort to mold it to

the shape of a preconceived conclusion, you leave yourself pretty

vulnerable."

What about Commander Humes burning his original notes of

his draft of the autopsy protocol?

"It's

extremely unfortunate that he did; but I interpret this only as further

evidence of his lack of experience in medico-legal situations.

I

can't believe that there's anything sinister about it as some of the

critics would have you believe. Commander Humes simply did

not

appreciate that this was not just another hospital autopsy and that

every note or memorandum should be saved for later scrutiny."

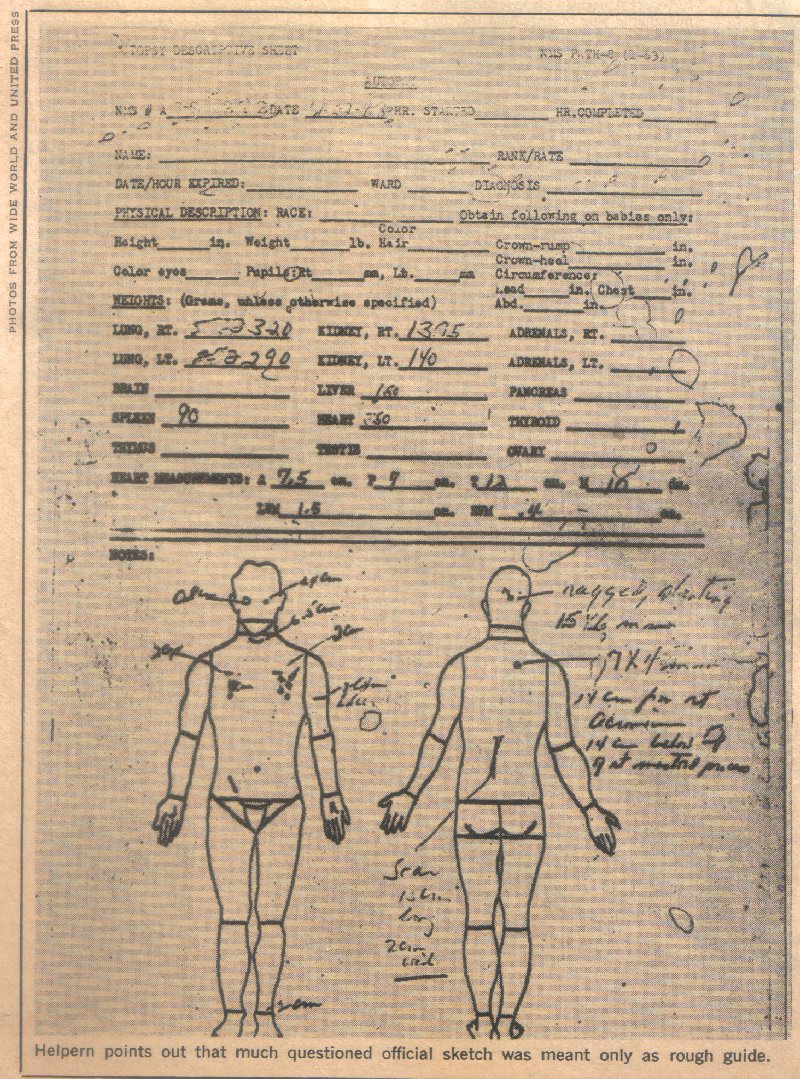

Some

of the critics of the Warren Commission Report have attempted to

bolster their attacks by alleging that Commander Boswell's drawing (a

portion of Commission Exhibit 397) shows the bullet wound in the back

of the neck as being down about the level of the shoulder blades.

Is this significant?

"It's significant in that it

demonstrates the total ignorance of the critics in the matter of

autopsy procedures. We don't need to spend any time on trivia

like this; but for information, this is simply part of the work sheet.

It contains two purely schematic drawings of the human

figure,

one front and one rear, in what is known as the 'anatomic position.'

The doctor doing the autopsy uses them as a shorthand way of

making notes on what he observes during his external examination of the

body. Commander Boswell sketched in a number of observations,

including the surgical scars, the old scar from the President's back

operation and the bullet holes. No one ever pretends that

these

markings are drawn to scale. To take the time to do this

would

defeat the entire purpose of this shorthand way of making notes.

The written material in the autopsy protocol is what matters."

Some

critics have alleged some sort of duplicity because an FBI report dated

December 9, 1963, and another one dated January 13, 1964, apparently

contain information which is not consistent with the formal autopsy

protocol.

"This is more trivia and underbrush. What

difference does it make what these two FBI reports said? The

controlling factor insofar as the medico-legal phase of the

investigation is concerned is the autopsy protocol itself.

There

was undoubtedly conversation going on in the autopsy room.

The

FBI agent there probably heard the doctors agonizing over their

inability to find the bullet. He observed them trying to

probe

the neck wound. He heard their speculations that the hole in

the

back of the neck was both

a

wound of entrance and a wound of exit. To me, all that these

particular FBI reports show is exactly what we have mentioned before :

at the time the autopsy was finished, the doctors thought they were

dealing with only three bullet holes, two in the head and one in the

back of the neck."

Where

did the Warren Commission, as distinguished from the autopsy surgeons,

fail to clarify the medical issues of the President's death?

"It

failed tragically because it did not have sufficient knowledge in the

field of forensic medicine to even appreciate the need to call in an

expert with experience in bullet wounds in the body. This

lack of

knowledge is evident in the official report itself. For

example,

it contains thousands of exhibits in eleven volumes. They

include

all sorts of meaningless pictures of Marina Oswald. Oswald's

mother, Oswald as a young boy. Jack Ruby's employees or girl

friends in varying states of attire, and nine X-rays of Governor

Connally's body.

"The X-rays of President Kennedy's body,

however, were not considered significant enough to the entire

investigation to be filed as exhibits to the report. The same

holds true of the black and white and the color pictures of the bullet

wounds. These were never seen by the Commission members, its

staff, or even the autopsy surgeons before the report was finalized.

The Commission members, its staff, or even the autopsy

surgeons

before the report was finalized. The Commission said it would

not

'press' for the X-rays and photographs because these would merely

'corroborate' the findings of the doctors, and that considerations of

'good taste' precluded these from being included.

"Well, you see,

there was nothing that offended 'good taste' in the nine X-rays of

Governor Connally's body [Commission Exhibit 691]; so this great

curtain of secrecy that was pulled down on the X-rays and pictures of

the President's body added more explosive fuel to the fire of doubt.

There have been intimations that these X-rays and pictures

had

gone the way of Commander Humes' notes; and it was only after

considerable public pressure built up that the pictures and X-rays were

turned over to the National Archives by the Kennedy family in November

of 1966; but they are still shrouded by this great curtain of secrecy.

Secrecy is the natural culture medium for suspicion."

Why didn't the examination by the Navy doctors of the

X-rays and pictures in November of 1966, still the doubts of the

critics?

"Let's

come back to our analogy of the seven-year-old violin player.

We

sit him down in front of an electronic microscope and ask him what he

sees on a slide. He says: 'I don't see anything.'

We then

jump to the conclusion that there is nothing there because an

inexperienced eye can't see anything there."

What might these X-rays show to an experienced observer

that could have been completely overlooked by the nonexpert expert?

"Who

knows? Probably absolutely nothing. I don't like to engage in

rank, blind speculation; so I can only explain how I would approach

them. My first interest would be to see whether there could

be

another bullet or fragment of bullet in the body which has not been

accounted for.

"Remember that the Warren Commission

concluded that the preponderance of the evidence indicated that three

shots altogether were fired. Only one relatively intact

bullet

and the fragments of a second bullet were found. This leaves

a

missing third bullet. I definitely do not agree with the

Commission's conclusion that only two bullets cause all the wounds

suffered by President Kennedy and Governor Connally; but we'll pass

that for the moment.

"Since

the X-rays of the President's body were not filed as exhibits, we must

rely entirely upon the observations of the Navy doctors that they

skillfully eliminated the possibility that a third bullet, or a

fragment of some bullet, did not enter the body and somehow meander

down to come to rest in some illogical remote spot.

Apparently,

the doctors did not feel confident enough to rely on the X-rays during

the autopsy when they went probing, for the bullet that was found on

the stretcher in Parkland Hospital. They have now been quoted

publicly as saying that they did have the X-rays available to them that

night. Bullets do have a funny habit of showing up in the

most

astounding places in the body.

"I would also look for trace

flecks of metal that might indicate another head wound. This

possibility is extremely remote; but it still exists. Often,

quite often, wounds of entrance in the head are completely overlooked

because they are covered naturally by the hair. The wound may

barely bleed at all. If you don't take a comb and go over the

entire scalp, inch by inch, separating the hair carefully and

meticulously, it's easy to miss a head wound entirely. There

is

no evidence that this type of examination was made."

Would the X-rays help establish whether the two wounds

in the neck area were wounds of entrance or of exit?

"No, I would not expect them to be of help on this

question."

What about the black and white and the color photographs?

"These

could be of considerable interest and value. A lot would

depend

on their quality and how they were exposed. Hopefully, they

could

shed considerable light on the neck wounds. I would, of

course,

be interested in what the pictures of the rear neck wound would show;

but I would be particularly interested in seeing whether the pictures

of the throat wound are good enough to permit it to be evaluated and

possibly reconstructed."

Where else can the Warren Commission be faulted for what

it did or failed to do?

"Again,

it committed a grievous error of omission by failing to call in someone

who knew something about bullet wounds in the body. This led

them

into the final trap of buying Assistant Counsel Arlen Specter's theory

that the same bullet which passed through the President's neck was the

bullet that also wounded Governor Connally, shattering his fifth rib,

fracturing a bone in the wrist and finally coming to rest in his thigh.

Now, this bizarre path is perfectly possible. When you are

working with bullet wounds, you must begin with the premise that anything is

possible; but Mr. Specter and the Commission overlooked one important

ingredient.

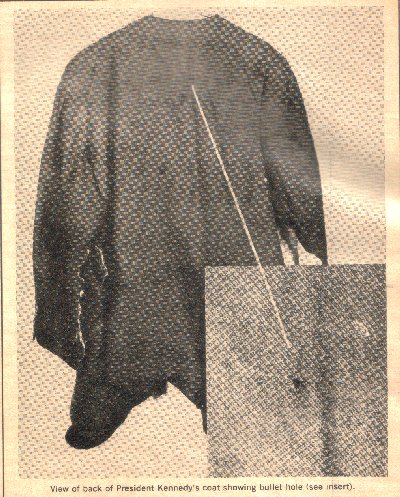

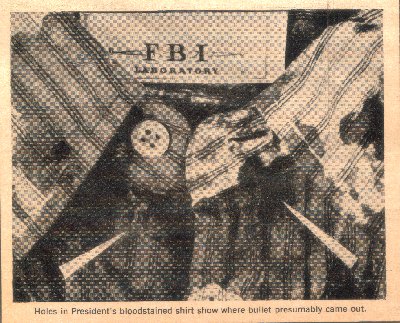

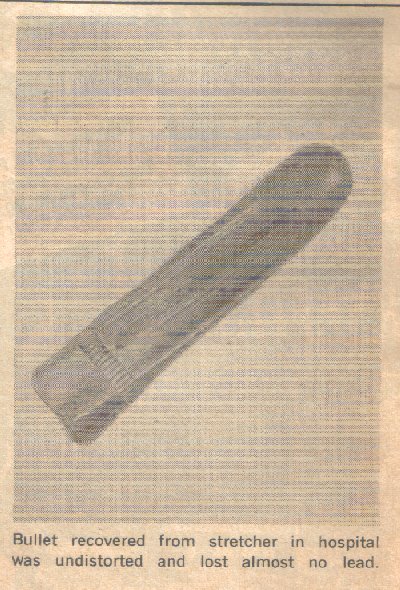

"The

original, pristine weight of this bullet before it was fired was

approximately 160 to 161 grains. The weight of the bullet

recovered on the stretcher in Parkland Hospital (Commission Exhibit 399) was reported by the Commission as 158.6 grains. This

bullet

wasn't distorted in any way. I cannot accept the premise that

this bullet thrashed around in all that bony tissue and lost only 1.4

to 2.4 grains of its original weight. I cannot believe,

either,

that this bullet is going to emerge miraculously unscathed, without any

deformity, and with its lands and grooves intact."

Does this shed any light on the other of the shots?

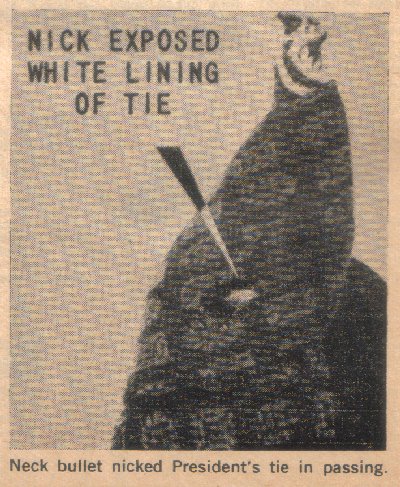

"In

my opinion, this was the first bullet that was fired. It

passed

through the President's neck, exited from the throat wound. and was

stopped by his clothing. I've seen this exact thing happen hundreds of

times. Remember that, next to bone, the skin offers greater

resistance to a bullet in its course through the body than any other

tissue. The energy of the bullet is sometimes spent so that

it

can't quite get out through the final layer of skin, and it comes to

rest just beneath the outside layer of skin. If it does get

through the skin, it may not have enough energy to penetrate even an

undershirt or a light cotton blouse. It has exhausted itself

and

more or less plops to a stop."

What about the Commission's conclusion that this bullet

was found on Governor Connally's stretcher in Parkland Hospital?

"It's

based on tortured evidence, or inconclusive evidence, to say the least.

No one will ever know for sure which stretcher this bullet

came

from. In my opinion, the probabilities are that it fell out

of

the President's clothing while the doctors were administering to him in

the hospital. For the sake of argument, however, let's

assume that

it was found on the Governor's stretcher. This still does not

rule out the premise that it was the first bullet that passed through

the President's neck. That spent bullet could just as easily

have

taken an erratic jump out of the President's clothing and lodged in

Governor Connally's clothing. These things happen with

bullets.

Sometimes they get through the final layer of skin and hop

limply

about at all arcs of the circle and at all angles to the wound of exit."

Do you agree with Governor Connally that he was struck

by the second

bullet?

"Yes,

I definitely do. His testimony is most persuasive.

I just

can't buy this theory that this beautifully preserved first bullet

which passed through the President's neck also got tangled up with the

Governor's rib and wrist bones. In my opinion, the second

bullet,

which wounded Governor Connally, is the one that is missing."

And the third?

"The

third one quite obviously is the one that caused the President's

massive head wound, and his death. Also, either a fragment

from

this bullet, or a piece of skull, caused the cracking of the windshield

and the dent in the windshield chrome on the interior of the limousine,

provided these marks on the car were not already present at the time

the shooting began."

Assistant Counsel Arlen Specter's creation

of the theory that a "single bullet" passed through the area of the

President's neck and went on to inflict all of Governor Connally's

wounds was necessitated, so he thought, by the Zapruder movie.

This "one-bullet" theory is perhaps the most amateurish

conclusion in the entire Warren Commission Report, and regrettably, it

permits the brand of "doubtful" to cloud the genuine, bona fide

Commission findings.

Abraham Zapruder is now undoubtedly the most

famous amateur movie photographer in all history. As he stood

in

Dealey Plaza aiming his home movie camera in an easterly direction, he

caught and recorded the Presidential motorcade as it proceeded north on

Houston Street, to make its turn west on Elm Street. This

innocent, famous home movie ended up by leading Mr. Specter and the

Warren Commission into an unfortunate trap.

Even those who have

purported to study the work of the Commission in considered hindsight

are still mesmerized by the beguiling and misleading power of the

Zapruder movie. For example, in its November 25, 1966 issue,

"Life" magazine innocently perpetuates the error. Its article

reads: "Of all the witnesses to the tragedy, the only unimpeachable one

is the 8-mm movie camera of Abraham Zapruder, which recorded the

assassination in sequence. Film passed through the camera at

18.3

frames a second, a little more than a twentieth of a second (.055

seconds) for each frame. By studying individual frames, one

can

see what happened at every instant and measure precisely the interval

between events."

The error that trapped the Warren Commission as well as

"Life" magazine is that there is nothing at all precisely measured

by the Zapruder film.

The nearest thing to a precise,

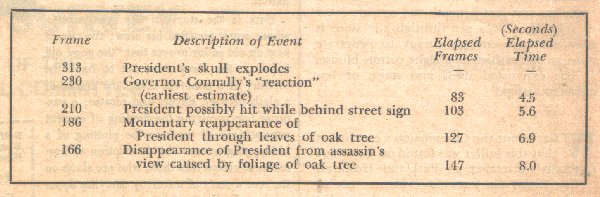

objective event which the film records is at Frame

313, which shows the

President's skull exploding as a result of the bullet that passed

through his head. Every other item purportedly measured by

the

Zapruder film is imprecise

because it must be evaluated and speculated upon through factors and

calculations which involve unknown quantities.

One

of the most common pitfalls in any investigation is the 'timetable

trap." The investigator becomes mesmerized by either a clock

or a

calendar and ends up with a conclusion that two and two are five, or

that some Florida oranges are red because Washington Delicious apples

are also red. This is exactly what happened to Mr. Specter

who,

unfortunately, was able to sell his erroneous theory to the Commission.

Some

time after the investigation into the President's death began, the FBI

staged a mock re-enactment of the assassination, which was geared to

and scripted by the Zapruder movie. An FBI agent was

stationed in

the sixth-floor window of the Texas School Book Depository Building

with a camera geared to the telescope lens of the Mannlicher-Carcano

rifle found at this same window minutes after the assassination.

An effort was made to synchronize

the Zapruder movie with what the assassin presumably saw from his point

of vantage at the sixth-floor window as the Presidential caravan moved

along its historic route.

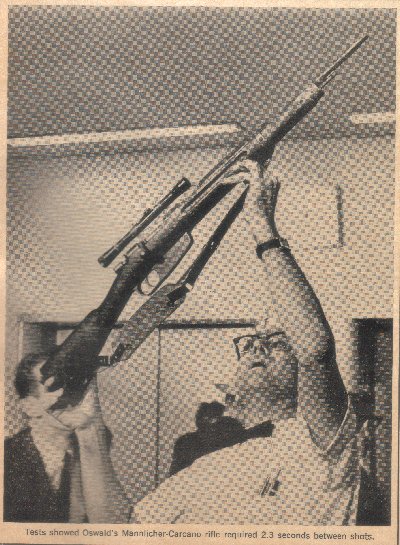

It had previously been determined that

the Zapruder camera ran at the speed of 18.3 pictures or frames per

second. The timing of certain events, therefore, could be

calculated by allowing 1/18.3 seconds for the action depicted from one

frame to the next. Other tests had also determined that this

Mannlicher-Carcano rifle required a minimum of 2.3 seconds between each

shot fired.

Each frame of the Zapruder film was given a number,

Number 1 beginning where the motorcycles leading the motorcade came

into view on Houston Street, Combining the FBI re-enactment with the

Zapruder movie, it was concluded that the assassin had a clear view of

the President from his sixth-floor window as the limousine moved up

Houston Street, and for an additional one hundred feet as the

Presidential car proceeded west on Elm

Street. At a point

denoted

as Frame 166 on the Zapruder

film, the assassin's view of the President

became obstructed by the foliage of a large oak tree.*

*One of

the most incredible statements of the entire report appears on page 97:

"On May 24, 1964, agents of the FBI and Secret Service conducted a

series of tests to determine as precisely as possible what happened on

November 22, 1963.... The agents ascertained that the foliage of an oak

tree that came between the gunman and his target along the motorcade

route on Elm Street was approximately the same as on the day of the

assassination." The report does not say how this was

"ascertained."

The

President's back reappeared into view through the telescopic lens on

the rifle for a fleeting instant at Frame

186. This momentary

view was permitted by an opening in the leaves of the tree; but they

closed to again obscure the view of the President's back through the

telescopic sight until the car emerged from behind the tree at Frame 210.

The Commission implies that one of the difficulties in

interpreting the Zapruder film is that the President's car begins to

disappear behind a road sign reading "Stemmons Freeway Right Lane" at

approximately Frame 193.

At Frame 206, the

President's hand

is

still raised as he disappears behind the street sign. He

reappears in the film at Frame 225.

As a matter of fact, it

is

really not essential to the evidential value of the film whether the

President was or was not out of sight for some 30 to 32 frames.

There are those who viewed the Zapruder movie who thought that the

President looked as if

he was hit through the neck when he reappeared from behind the street

sign at Frame 234.

"Life" summarizes the subjective

factor

of interpretation by saying: "Specter sees Connally wincing in Frame 230. 'Life' photo

interpreters think he looks unharmed, as

does Connally himself."

Still, Mr. Specter labored under the illusion that the

Zapruder movie gave him a stop-watch precision measurement of events

that took place , not

in the Presidential limousine, but in the Texas School Book Depository

Building over one hundred feet back up Elm Street.

Mr. Specter did not

believe that he could solve of orienting the Zapruder movie to the

minimum time required to fire two shots from the Mannlicher-Carcano

rifle without adopting the "one-bullet" theory. The 2.3

seconds required to fire two shots from the rifle worked out to 42.09

frames of the Zapruder movie. Even assuming that the

President had been hit in the neck while he was behind the street sign

at, say, Frame 210, it would

not be possible for a second shot to be

fired until Frame 252.09.

This presented a difficult impasse, provided the

"timetable" supplied by the Zapruder movie was correct. Mr.

Specter assumed that this "timetable" was accurate and then adopted the

"one-bullet" theory to get around its limitations. Otherwise,

he was faced with the awkward admission that two guns were used

instead of one.

His better procedure would have been to carefully

analyze his "timetable" in an effort to understand exactly what he was

working with. By beginning with Frame

313 - the only

objective point of reference in the entire film where the picture of

the President's exploding skull was recorded - we can set up a reverse timetable by working

backward (See box below):

What does this reverse timetable

prove? It proves exactly the same thing as the forward timetable of

the Zapruder film - which is exactly nothing. Nothing is

proved because we do not know when the President and Governor Connally

were struck by the first and second bullets. There is

absolutely nothing in the frames of the movie to give us any precise

measurement. In the first place, we are in a quandary of

uncertainty as to when the President and the Governor

"reacted" to their respective wounds. It has already been

clearly established that different observers of the Zapruder film have

reached different opinions as to when these "reactions" took place.

We are dealing with subjective

evaluation, which completely kicks out the concept of any precise "timetable."

The next great error

that was committed in attempting to use the Zapruder film as a

"timetable" was the assumption that the President and the Governor

would have some visible reaction to their wounds at almost the exact instant that

the wounds were sustained. There is absolutely nothing in

medicine to indicate that this assumption is correct. As a

matter of fact, what is known about reaction time generally indicates

that the assumption may not

be correct at all.

It must readily be

admitted that the reaction time of any person to a bullet wound is a

purely speculative entity. No one has yet conducted a series

of experiments so that a set of rules governing reaction time to bullet

wounds can be formulated.

Studies have been made

of certain other types of reaction time in the field of

automobile-accident reconstruction where elaborate tests have been

given to drivers under controlled conditions. It has been

established that between the time the driver perceives a dangerous

event and the time that he applies his brakes or begins other evasive

action, an average reaction period of two-thirds to three-quarters of a

second elapses. In some individuals, this reaction time is

well over one full second. There is always some "drag" or

reaction time involved between the stimulus and the reaction to

stimulus. This is true, even though this type of stimulus is something

that the driver has been conditioned to expect and which he must

anticipate by the nature of the testing situation.

No one knows whether

there is an analogy between driver reaction time and bullet-wound

reaction time. It can be argued plausibly that driver

reaction time involves a conscious thinking process, whereas the

reaction of the body to a bullet is more nearly analogous to an

autonomic, reflex type of action. There are, however,

hundreds of reported cases in which the person shot apparently does not

realize that he has been shot for a period of several minutes.

He may continue to perform a number of complex, highly

co-ordinated functions for a substantial period of time before

collapsing to lose consciousness or to die.

Furthermore, Governor

Connally's reaction time to his wounds may have been hit at Frame 230

of the Zapruder film. He may have "reacted" immediately, so

that his "reaction" can still be observed by viewers of the movie.

this does not mean at all that the President could not have been shot

through the neck before Frame 166

when his back disappeared behind the

leaves of the oak tree, or at Frame 186

when his back reappeared

momentarily, and his observable reactions appear on the movie after

Frame 225 when the

President emerges from behind the road sign.

There is absolutely

nothing in the "open-end" Zapruder movie "timetable" to rule out the

possibility or even the probability that the President was shot through

the neck before Frame 166.

The error in using the Zapruder

film was in the assumption that the President would have to "react"

instantaneously to the neck wound in such a manner that his reaction

could be observed in the movie. The Zapruder film is not really a

"timetable" after all, because it can help establish the "location" of

only one "station" along the "railroad." It does not help us

pinpoint the other two important stations, nor does it tell us when the

train got there. We can use the Zapruder "timetable" to

conclude that the train got to one station probably no later

than Frame 225. It

reached the second station no later than

Frame 234. We

cannot tell from the Zapruder film what the

train was doing before these two locations, or even where our floating

stations one and two are located.

It was not necessary

for Mr. Specter to devise, nor for the Commission to buy, the

"one-bullet" theory to eliminate the necessity of adopting the

embarrassing premise that two

rifles were used to do the shooting instead of one.

Dr. Helpern's theory of

three separate bullets causing three separate wounds, two in the

President's body and one in Governor Connally, is not at all

inconsistent with the Zapruder movie when the movie is properly

interpreted as being nothing more than an open-end, one-station

timetable where the separate elements of time, distance and location

have been confused.

What about the "wound

ballistics experiments" conducted at the Edgewood Arsenal?

"Well," Dr. Helpern

responds, shaking his head in disbelief, "the mere fact that they felt

constrained to perform these tests in the first place shows a total

lack of knowledge on the subject of bullet wounds in the body.

They went down there and tried to rig up dummies that would

simulate the President's head and neck area. They took human

skulls, filled them with gelatin and covered them with goatskin and

hair. They rigged up a dummy with gelatin and animal meat to

simulate the neck area of his body. Then they got a goat to

simulate Governor Connally's body. They took the rifle found

in the Texas School Book Depository Building and began firing into

these dummies. All they proved was that they proved

absolutely nothing. One of the experts was utterly surprised

that a bullet could cause the massive wound in the President's head.

His surprise alone indicates his limited experience.

"We have all kinds of

cases in our files that show what bullets can and have done in the

human body. So does everyone else who is active in the field

of forensic medicine. For example, Dr. LeMoyne Snyder has a

case that almost duplicates the President's head wounds in every

respect. It arose out of a bank holdup in Michigan.

A dentist who had his office on the second floor of a

building directly across the street from the bank went to the window to

see what the trouble was. He saw one of the bandits running

down the street, with people yelling after him. The dentist

was quite a deer hunter and kept a rifle in his office. He

reached for his rifle, raised the window and hit the bandit in the back

of the head with a single shot. By that time, the bandit was

just about the same distance away as the Presidential limousine was

from the sixth-floor window of the Texas School Book Depository

Building when the first shot struck. The head wounds this

bank bandit sustained were almost identical in every respect to those

of President Kennedy.

"Nevertheless, the

Commission chose to rely on the synthetic tests at the Edgewood Arsenal

to support its conclusion that a single bullet probably caused the

wound through the President's neck and all of Governor Connally's

wounds. This was done even though one of the three experts,

Dr. Light, testified that the anatomical findings alone were

insufficient for him to formulate a firm opinion on whether the same

bullet did or did not pass through the President's neck wound first

before inflicting all the wounds on Governor Connally."

Is there anything in

the overall picture to cast serious doubt on the principal conclusions

by the Commission?

"Of course, I haven't

seen the pictures and the X-rays of the President, but on the basis of

the evidence that has been made public, the Commission reached the

correct opinion that all three bullets were fired by one rifleman from

the sixth-floor window of the Texas School Book Depository Building.

The unfortunate autopsy and other procedures have merely

opened the door and invited the critics to enjoy a Roman holiday at the

expense of the dignity and prestige of the country as a whole."

"The fact that a

rigorous cross-examination of the three autopsy surgeons would have

ripped their testimony to shreds does not necessary mean that their

conclusions were totally

wrong in its opinion that all the shots came from the Depository

building. What it means is that the Commission members

themselves set the stage for the aura of doubt and suspicion that has

enveloped their work.

"The Commission of

course, was an unusual creature. It was itself a synthetic

entity. It was extra-judicial, extra-executive and

extra-legislative. It was supposed to be a public forum of

the courtroom because the normal forum of the courtroom was wiped out

when Jack Ruby killed Oswald. If Oswald had lived, all the

evidence about the President's death could have been aired in the

courtroom and all the witnesses would have been open to

cross-examination. In its procedures, the Commission failed

to supply anything that would fill the disastrous void left when the

right or motive to cross-examine the witnesses was wiped out.

They did not provide for the essential Devil's

Advocate."

"The biblical saying

that 'a man is judged by his work' may be appropriate. The

Commission's work opened the door and invited the critics to flood in."

Is there anything

specifically Dr. Helpern would like to see done at this point?

"It may well be too

late to do anything, since the primary evidence is gone.

There is a possibility, however, that the X-rays and

photographs of the President's wounds might contain some clarifying

information. I would certainly feel more comfortable about

the Warren Commission's findings if a group of experienced men, who

have had a great deal of practical work in bullet-wound cases, could

take a look at these X-rays and pictures. I have in mind men

like Dr. LeMoyne Snyder, author of 'Homicide Investigation,'

Dr. Russell Fisher, the medical examiner for the State of

Maryland, Dr. Frank Cleveland in Cincinnati, and Dr. Richard Myers in Los

Angeles. These men are all members of the American Academy of

Forensic Sciences. These pictures and X-rays might, and I

emphasize might,

settle the questions raised by the critics once and for all.

"The tragic thing is

that a greatly loved President was not given the same type of expert

medical attention and medical respect in death that he received in

life. When he was having back problems, he properly consulted

the leading experts in the field of orthopedic surgery; but, you see,

in death, the task of evaluating his bullet wounds was not given to

experienced experts in this field. It was still the old saw

that an autopsy is an autopsy is an autopsy, and anyone can do it,

particularly as long as he is a pathologist."

What about the portions

of the autopsy protocol that have not been released to the public?

"There, I think." Dr.

Helpern answers, "are personal matters that should be left entirely to

the family, although I do think that the public is entitled to the most

expert and definitive determination possible on the bullet wounds that

caused death.

"I know it has been

argued that, since the question of whether the President did or did not

have Addison's disease was injected as an issue into the 1960

Presidential campaign, the public is entitled to know if any findings

at the autopsy tended to substantiate this allegation.

"Some of my collegues

also argue that if the autopsy findings did show a deterioration of the

adrenal glands, which would be evidence of Addison's disease, it is a

missed opportunity for showing the progress of medicine in general to

fail to disclose it. A person suffering from Addison's

disease can now be placed on medication so that the disease can be

controlled in much the same manner that diabetes is

controlled by insulin. This, of course, was not true a

generation ago. These fellows continue that it would

dramatically show medicine's progress if a man with Addison's disease

could be treated so successfully that he could function well enough to

perform the duties demanded by the office of President of the United

States.

"I still go along with

the feeling that any disclosure in the autopsy findings over and above

the bullet wounds which produced the President's death must be

considered a private matter for the family to do with as they

personally desire."

Costella Combined

Edit Frames

Zapruder film

frames referenced located here

JFK Doctors Are Dying

Read story here

Lies

about the Kennedy and Forrestal Deaths

Read story here

This one's for John

Barbour, with love.

Lorie Kramer

seektress@seektress.info |