Mario Lanza, 27-year-old tenor from Philadelphia, has

become almost overnight one of America’s best-known singers. He has long-term

contracts with RCA-Victor Records, with Arthur Judson for concert appearances,

and with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. His most recent movie appearance was in “that

Midnight Kiss.” Next September Lanza will make his debut at La Scala in Milan,

with Victor de Sabata conducting.

Last August the American Legion met in Philadelphia for

that largest encampment it has ever held. It brought one million visitors to

town. That was the week chosen by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for the premiere of the

motion picture, “That Midnight Kiss,” in which Miss Kathryn Grayson and I were

starring with Ethel Barrymore and Jose Iturbi. Philadelphia was chosen because

of the scene of the film was laid in Philadelphia where I was born January 31,

1922, at Seventh and Christian Streets in “Little Italy,” and the story of the

film had some incidents of my youth. Philadelphia’s “Little Italy” houses far

more people of Italian descent than most of the cities in Italy itself.

In

the early 20s, at the height of the prohibition era, Philadelphia’s “Little Italy”

was probably the roughest, toughest, most vicious part of the United States.

Gangsters, bootleggers, murderers, racketeers chose it for a battleground.

Hardly a day went past without a shooting. As a little boy in the streets I

heard the bullets whiz many times. In those days hot Latin blood literally

boiled in the streets and alleys, and no one knew what the day would bring

forth. I often wonder how I came through it alive, as many innocent bystanders

were killed. Finally the police, the F.B.I., together with the stable citizens,

who composed the better part of the community, gained the upper hand. “Little

Italy” is no longer a gangster’s paradise, but is filled with citizens who love

America and are so proud of their citizenship that few of the younger

generation, unfortunately, can speak Italian.

While

some 30,000 Legionnaires were parading for twelve hours through Philadelphia’s

streets, another celebration was occurring in “Little Italy.” The Mayor of

Philadelphia, Hon. Bernard Samuel, the president of the Chamber of Commerce,

Ralph Kelly, and the chairman of the Chamber of Commerce, Arthur C. Kaufmann,

together with other noted Philadelphians, took me in a motorcade down to my old

home district, where a fiesta was being held as only Italians can hold fiestas,

to celebrate my entrance to the movies in “That Midnight Kiss.” The streets were jammed with cheering

neighbors and friends. Rhadames in “Aida,” returning after his victory in

Ethiopia, could not have had a more boisterous welcome. It seemed incredible.

Only a few years ago I was a piccolo ragazzo playing around the street and now

the whole town was hailing me as a hero. Do you wonder that I was so

emotionally moved that I wept with joy for three hours that night?

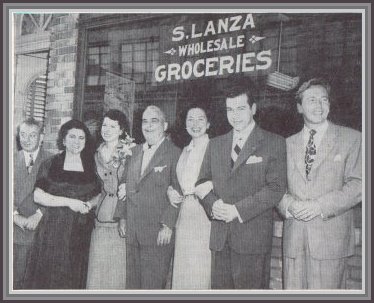

A fiesta in South Philadelphia's "Little Italy" welcomed Mario Lanza home at the time of the premiere showing of "that Midnight Kiss". In front of the store over which the newly famous tenor was born are gathered: (l. to r.) Lanza's father and mother (Mr. and Mrs. Cocozza), Mrs.Mario Lanza, Philadelphia's Mayor Bernard Samuel, Kathryn Grayson (Mrs. Jon Johnston), Mario Lanza, Jon Johnston.

My

immigrant father, Antonio Cocozza, was a wounded and incapacitated veteran of

World War I, who captured the first German prisoners in the Argonne. My

grandfather, Salvatore Lanza, still conducts a grocery and trucking business at

Seventh and Christian streets, and it was over his store that I was born.

Few

Americans can sense the Italian’s love for opera It is the result of centuries

of development. Opera is in every Italian’s blood. I am told that in Italy

around the opera houses there are push carts in the streets loaded with opera

librettos just like peanut stands around a ball park in America. The enthusiasm

for baseball in our country is mild compared with the Italian’s love for opera.

Scores of Italians with an irrepressible yen for producing opera have gone

broke repeatedly.

My

father was a great opera enthusiast and had a large collection of records of

his favorite singers. I heard these from the time I could first hear a clock

tick. They were as much a part of my life as spaghetti and chianti.

Father

used to buy his records at a store operated by a remarkable character known as

Pop Iannarelli. He was the Victor record dealer in our district. He had an

amplifier in front of his store. When he put on a new record, the whole

neighborhood was turned into an opera house. You could hear that amplifier

winter or summer three blocks away. Nobody shouted “Stop that noise,” but

“Bravo! Bis!” (Splendid! More! More!)

Pop

Iannarelli took a great interest in me. He was a world of operatic inspiration

and information. To be with him was like being brought up on the stage of an

opera house. When I was ten, I could reel off the plots of fifty grand operas

just as the average American kid could give you baseball scores. I also knew

the principal arias of all these operas. When Pop Iannarelli put on records of

“Vesti la giubba” or “Una furtive lagrima,” I seemed to break out in goose

pimples from head to foot.

At

the same time I was just a neighborhood kid interested in fun, sports and not

without the inevitable mischief that shadows all small boys. I had my little

street gang and I was the leader. Only the other boys looked upon me as a kind

of “opera mad” high brow, while the other gangs were having difficulties in

evading the police as well as the bullets of the real gangsters and racketeers

who daily shot it out in “Little Italy”.

My

school marks at the public school and at the South Philadelphia High School

where the tireless music supervisor, Jay Speck, had charge of the music, were

average but not brilliant. I learned something of musical notation under Mr.

Speck, but never took any special part in the school musical activities. That

was probably because the school never had a grand opera company.

I

went in for sports, became a boxer, a baseball player, and a semi-professional

football player. I was also a weight lifter. At 18 I could lift 200 pounds. I

earned my living for some time in football. I was offered a college scholarship

because of my success at football, but getting an education in that way did not

appeal to me. To sports and to my musical interest I probably owe my escape

from juvenile delinquency in that vicious district of Philadelphia in which I

grew up.

My

parents, noting my interest in music, wished to give me lessons. Our family was

poor but they got together $75.00, bought me a violin and sent me to the

Settlement Music School on Queen street supported by wealthy Philadelphians.

Johann Grolle, a former director of the Curtis Institute, was its guiding

spirit. Somehow I did not take to the drudgery of early violin study and when

the teacher discovered that I was playing by ear instead of by note, he made a

remark that made me fly into a temper and I threw the violin out of a third

story window. It smashed on a passing rubbish truck and my career as a

violinist was ended.

My

parents looked upon me as incorrigible, for the loss of the $75.00 instrument

came as a calamity to the family. Later, they sent me to the same school to

study piano with no better results. At least however, I did not throw the piano

out the window.

I

did not even dream that I had a singing voice until I was nearly twenty. Many

young folks who are unable to afford a good teacher, wait around bemoaning

their fate until it is too late. If I had done that, I would have lost years of

time. Get the best records of great singers and listen to them over and over

again, hundreds of times. Listen to the fine, pure and relaxed production.

Always sing mezza voce (half voice) with absolutely no strain at first,

and then some day you may find as I did that you really have a voice.

Read

everything you can about the voice and then use all the intelligence at your

command in applying it to your own case. I think that many vocal aspirants do

not realize how much all-important collateral information can be gained from records,

books and magazines that even the best of teachers do not have time to take up

in lessons. Somehow I picked up a surprising amount of musical information, not

in the orthodox conservatory manner, but by tapping every possible source and

impressing it upon my mind.

One

day when I was between 19 and 20 years old, I was playing the Caruso record of

the great tenor solo in Puccini’s “La Fani ulla del West” (Girl of the Golden

West) and I felt an impulse to sing with the record.

I had

had no vocal training of any kind up to that time, save that which was stored

up in my subconscious mind by hearing countless records. I had never thought that I could sing and

the sounds that were coming from my throat amazed me. It was as though something

pent up for years was now gushing out like a mountain spring.

I

was dazed. It seemed a miracle to me. I sang with Caruso records incessantly,

hardly taking time to eat or sleep. I had found my voice. I could hardly

believe it. Even when my excited father came in and said, “Why, you have a

great voice. You will have to study,” I was incredulous.

I

did not know how to produce tone, but I knew the kind of tone I wanted, and

when I reached the highest notes, veins stood out upon my forehead and my face

turned blood-red. Finally, one day my father, who had been listening to me

without my knowing it, came in with tears in his eyes and said, “You cannot

waste any more time. You must go to a vocal coach at once.”

“But,”

I said, “Papa, that is not singing, it is only noise.”

“Well,”

he replied, “if that is only noise, it is the most beautiful noise I have ever

heard.”

He

sent me to Miss Irene Williams, a well-known coach in Philadelphia, who drilled

me in some of the leading arias from the operas. I had up to that time,

however, no fundamental lessons in actual voice training to teach me how to

handle my voice to best advantage. Vocal coaching, which drills the singer in

the roles he must sing, is quite different from voice training. The voice

trainer is like the master violin maker who takes rare woods and forms them

into a master instrument as did Stradivarius or Guarnerius. Both the voice

trainer and the vocal coach are indispensable.

My

grandfather, however, contended that I was only wasting my time singing. As I

was then working for him in his grocery store, and in his trucking business, he

demanded that I devote my time exclusively to business. He could not understand

my dreams and what they meant to me. But my destiny was then clear and I knew

that I was intended to be a singer. In the meantime there was no alternative. I

had to drive Grand-dad’s trucks!