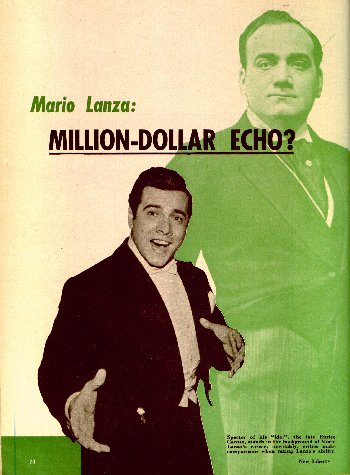

Along with Gorgeous George, Gargantua

and the miracle of television, a relatively untrained, highly self-centered,

heaven-blessed tenor who calls himself Mario Lanza must now take his place among

the show business phenomena of the decade. Few opera singers are more widely

known. Only a handful are equally affluent. And none has sung less frequently

in the hallowed halls of the chanted drama.

The 31-year-old

ex-Philadelphian, whose 1952 gross income should approximate one and a half

million dollars, possesses what some observers regard as one of the world's

finest natural voices. However, despite worshipful vagaries by his hangers-on

and an occasional hint from Lanza, himself, the Metropolitan Opera Company

indicates no intention of adding him to its roster. The less demanding La

Scala of Milan, aware of the singer's box-office magnetism, recently extended

to him a public invitation for a six-month season in 1953. While this bid may

turn out to be little more than inspired press agentry, the tenor's

appearance with La Scala would do much to legitimatize his reputation as a

bona fide grand opera star. At present his experience in the medium is

singularly limited: He has performed in only one operatic vehicle, Madame

Butterfly, sung twice with a New Orleans group in 1948.

Whether he does

appear at La Scala or not, Lanza, voicing conventional operatic arias and a

profusion of current ballads, is today heard by more people than hear any

other male singer with the exceptions of Bing Crosby and Perry Como. Secure

in gilt-edged MGM and RCA-Victor pacts, Lanza has been, perhaps unkindly,

described as a peacock who preens his feathers beside his Beverly Hills

swimming pool and delights in listening to the sound of his own voice on

recordings, every so often rending the California sunshine with screams of

delighted self-praise.

It would

probably be more humanitarian to excuse his coyness and ego as the results of

a pampered childhood than to blame him for a self-regard, which at times

appears to approach the colossal. Lanza's career has progressed with such

speed that he needs a breathing spell to catch up with himself, both

artistically and personally. The raw material of greatness is within him.

What he does with it still remains to be seen.

Nonetheless, it

well may be that this ex-football player is the best friend grand opera has

had since Caruso hit his peak.

In preparing

this article for New Liberty, I talked to Metropolitan Opera baritone Robert

Merrill. ";In his own way", said Merrill, "Mario is a great

credit to good music. He captures the imagination of a large portion of the

general public which never attends opera. He has interested many people in

fine music who might otherwise never discover its delights." This is

certainly true enough. Recordings of grand opera took a definite jump

following release of The Great Caruso, the movie which brought Lanza

star status. While critical appraisal of his work varied, public acceptance

of the new idol was pronounced. The movie took in close to one million four

hundred thousand dollars in 10 weeks at New York's Radio City Music Hall and

will continue earning dividends for years to come.

MGM's decision

to cast Lanza in The Great Caruso was made with some trepidation.

Jesse Lasky, owner of film rights to the tenor's life story, originally

planned to use Caruso recordings on the film's soundtrack. A small fortune

was spent in the sound laboratory filtering out unsuitable musical backgrounds

and surface noises in the ancient discs. But considerable portions of

Caruso's exquisite tone and quality were also filtered out in the process.

Then along came Lanza, a happy click in Toast of New Orleans and That

Midnight Kiss. There was no doubting the quality of his voice, but it

was a wild instrument, needing discipline and polish.

The decision

was up to Louis B. Mayer, then supreme boss at MGM. Mayer remembered two

previous pronunciamentos which had caused him considerable

embarrassment. In 1945 he proudly told all comers that Clark Gable's postwar return

to the screen in Adventure would prove the year's biggest

money-making movie. Instead, it was the season's greatest flop and almost

ended Gable's career. Then, in 1948, Mayer predicted the studio would be

fortunate to break even on Mario's first movie, That Midnight Kiss.

Undaunted by such official pessimism, the picture went right out and earned a

handsome dividend.

With increased

respect for Lanza's pulling power, Mayer decided to take a chance on Mario in

the role of the great Caruso. The casting was a daring stroke, but the

veteran executive knew he'd be criticized from some quarters no matter whom

he chose to impersonate the immortal Enrico. He was also aware that this

could be a star-making role if properly handled. In deference to Lanza's

minor league experience, the musical score was restricted to frequently

performed arias, the tunes of opera. Producer Joe Pasternak,

whose know-how had made a singing star of Deanna Durbin, hired Maestro

Spadoni, Caruso's own voice coach, to work with Lanza through months of

rehearsal. Selections were recorded and re-recorded until a small army of

experts had coaxed from Lanza the closest mimicry of Caruso of which he was

capable. All this caused

no special excitement at the studio. The sound stage was never flooded with a

sideline audience. Don Hartman, at that time an MGM executive, says

succinctly, "Who the hell wanted to hear a fat and hammy tenor sing

arias?" Hartman,

himself a highly successful showman, soon had his answer. The picture was

a bonanza. Word-of-mouth promotion outstripped even MGM's costly advertising

campaign in spreading the good news, and some fans returned to see the film

four and five times. Moreover, it brought back to the theaters a large

segment of the so-called "lost audience" principally taxpayers in

the middle-age bracket who had long ago lost the movie-going habit. Dorothy Caruso,

Enrico's pretty widow, was tactfully enthusiastic. Privately, however, she

confided her hopes that the screen one day would do better by her late

husband, both in script development and musical interpretation. Less reticence

has been shown by other members of Caruso's immediate family circle. Inflamed

by an MGM-Coca-Cola advertising campaign which flooded their native Italy

with posters combining Caruso with Coke, son Enrico Jr. and grandsons Enrico

and Roberto took their seething indignation to the Rome courts. Later, the

posters were covered over, leaving only a headless body gesturing towards a

Coca-Cola bottle top. That was only

half the Caruso's battle. Another court case is lined up against MGM for

allegedly filming Caruso's life without family permission. Complains Grandson

Enrico:"The

picture is full of historical inaccuracies. It gives the impression that

Caruso arrived in the U.S. almost an unknown, that America launched him, glorified

him and was responsible for his success. The picture denationalizes my

grandfather".

More pointedly,

the family regard Lanza as "just a beginner, with a crude, uneducated

voice, unworthy of Caruso". To critics who

minimize his performance, Lanza points out that Caruso at age 29 was no huge

success, that critical acclaim was not showered upon the tenor until his late

thirties. However,

sputter the critics in reply, at best Lanza's feat has been one of imitation.

No matter how mechanically excellent he may be, they insist, he is in no way

creative. Years of addiction to Caruso recordings have taught him every

inflection, every sob of every disc. Two men have

played key roles in the evolution of Mario Lanza: Sam Weiler and Enrico

Caruso. Caruso came first.  Parents Maria and Antonio Cocozza, daughters Coleen and Elissa, and wife Nancy,

pay surprise visit to Lanza set during making of his yet-to-be-released movie, Because You're Mine.

Mario's real

name is Alfred Arnold Cocozza. His father, Antonio, was decorated for bravery

with the American forces in World War I and has been on a total disability

pension ever since, his right arm rendered useless by a German bullet. To

supplement this income his wife worked as seamstress and corsetiere. They

lived pleasantly though frugally in a six-room house in south Philadelphia, lavishing

a tolerance upon their only son which he did little to merit.Few children

have been more expertly spoiled. Mario's mother rose at 5:30 each morning to

get to her garment-making job her father Cocozza served his son breakfast in

bed. In his late teens, the lad often slept until noon or later. A less

indulgent school teacher remembers the boy as "one of the biggest bums

that ever came into the public school system" - an uneasy liaison which

ended when Southern High School expelled Lanza for punching a member of the

staff. Mario says the teacher aroused his ire by calling him a

"dago", but he admits having been a notorious show-off and sometimes

obscene. "I must have been a little bastard, but I was always the

leader," he told an interviewer recently. Mario's mother,

Maria Lanza Cocozza (he eventually adopted her family name for his own

professional use), indulged the boy consistently. She bought him a violin

which he promptly tossed out a second-floor window. She acquired a piano but

he showed little interest. She taught him Italian in hopes he might one day

turn to singing. And she lavished upon him numerous recordings by Caruso.

From his earliest years, Mario had worshipped the operatic giant and in the

Cocozza home, the Caruso discs spun from dawn to dark and often far into the

night. Sometimes Mario sang along with the records, and by his early teens he

knew several arias by heart. And all these

years Mario did nary a single day's honest toil. Living off his father's

pension and his mother's hard-earned wages troubled his conscience not at

all. And it troubled his mother even less. "It's true

Mario never worked at anything until he finally found his singing

career," says Mrs. Cocozza, still attractively neat and full of sparkle

despite the rigors of life. "He was a big, 250-pound boy and I was

criticized for not sending him out to add to our income. But I do not believe

a child is born to provide money for his parents. Education and freedom to do

what God has enabled you to do - this is much more important for any child.

It was my own business if I wanted to stake him to whatever future career he

might choose." After departing

abruptly from Southern High, the husky youngster picked up a few dollars in

semi-pro baseball and football. But mostly he played ladies' man to the

damsels on the block, or stayed home and listened to Caruso on the

phonograph. After all, there was always food on the table and sometimes

breakfast in bed - so why work? While stories

of Mario's first important break vary, his maternal grandfather's disapproval

of the boy figures in all versions. Seems that Grandpa felt the time had come

for Mario to earn his keep. Grandpa had a temper. So Mario heeded the

pressure and apprenticed himself to a trucking company. "You pays

your money and you takes your choice" from here on in. Mario's mother

says a mutual friend arranged for conductor Serge Koussevitzky to grant the

lad an audition. Mario's chum and unofficial biographer, Ben Maddox,

dramatizes it somewhat, declaring Mario was ordered by the trucking company

to deliver a piano to the Philadelphia Academy of Music. "As he pushed

the piano out on the empty stage Mario was happily singing at the top of his

lungs," reports Maddox. "It so happened that Koussevitzky was

rehearsing the visiting Boston Symphony Orchestra in an adjacent hall.

Hearing this magnificent voice, Koussevitzky rushed out and snagged him as

his protégé' on the spot." Mario himself

puts it this way: "I was 20 and without a job when Grandfather insisted

I drive one of his trucks. I delivered a piano to the Academy of Music, where

Serge Koussevizky was rehearsing the Boston Orchestra. 'Sing for the famous

conductor!' I was told. I did, spontaneously. I sang an aria as nearly like

Caruso's recording of it as I could. Koussevitzky was so astounded he

launched me on a career at a concert of his three weeks later." Version number

three comes from Irene Williams, a Philadelphia voice coach. According to

Miss Williams, she and William Huff, a patron of the arts, arranged an

audition for the young tenor with Koussevitzky after a concert. The great

conductor was stretched out on the table in his backstage dressing room,

getting a rub-down, when Lanza was ushered in and ordered to sing the aria

from Pagliacci, Koussevitzky nodded approval and invited Lanza to

study on a Summer scholarship at the Tanglewood Music Festival in the

Berkshires. Lanza had taken

a few singing lessons with Miss Williams. He claims she tutored him only five

or six times. She insists he studied with her regularly for over a year, his

mother paying five dollars a lesson. At any rate, just prior to his joining

the Air Force, Lanza allegedly signed a contract granting the teacher 10 per

cent of his future earnings. When he failed to pay this, Miss Williams sued,

Lanza eventually settled the case out of court. At Tanglewood,

Lanza was at least consistent, concentrating on poker and women rather than

study. Still, he was signed to a representation contract by the Columbia

Concerts Corporation and accepted several minor bookings before donning his

uniform and going on duty as a military policeman. Lanza and the Air Force

failed to agree with each other and he has since been called the sloppiest

soldier in the command. He resented regimentation and missed his usual

breakfast in bed. By a stroke of luck, he was able to maneuver himself into

both stage and screen version of the Moss Hart Air Force show, Winged

Victory, and it was during shooting of the film on the 20th Century-Fox

lot that Mario (then a ponderous 287 pounds), had his first taste of life in

Hollywood. In January

1945, Lanza's post-nasal drip got him a medical discharge from the service. A

few months earlier, while working in the movie, he had been invited to dinner

at the home of Private Bert Hicks, one of his buddies in the show. Mario fell

instantly in love with Hicks' sister, Betty, and they were married soon after

his return to civilian life.  Enthusiast Lanza talks

fishing prospects during rare, between films vacation with wife and friends,

singers Andy and Della Russell.In May, Lanza began work on new film, The

Student Prince.

Betty, pretty and

dark-haired, still wears the six-and-a-half dollar ring which Mario slipped

on her finger at the civil ceremony before Beverly Hills Municipal Judge

Charles Griffin. Quite recently, however, Lanza presented her with a set of

costly jeweled guards which she places on either side of the original wedding

ring. Lanza is not

one to pinch pennies, particularly if he has only a few to pinch. His

accumulated army severance pay didn't last long with the always-hungry tenor

and his young bride ensconced in a plush suite at Gotham's Park Central

Hotel. But the fates have always smiled kindly upon Lanza, and now fate, in

the benevolent form of RCA-Victor, came along with an unexpected windfall. An

executive of the recording company, having heard Mario sing at a Hollywood

house party, paid him a three thousand dollar bonus simply to sign a contract

with the company. Not that RCA was in any hurry for Lanza to record. The

company merely regarded the bonus as an option on future exclusive services,

if and when he really learned to sing. It was, of

course, a gamble which is still paying off. Ironically, MGM Studios which

holds sole rights to Lanza's services as an actor, also manufactures

phonograph discs under its own label. But Mario can wax his songs only for

RCA, even though they may be ditties introduced in his MGM movies. This

infuriates the studio but it’s powerless to change the situation. Lanza proceeded

to run through the three thousand dollar bonus like a red hot knife through

ice cream. The Park Central always beyond their means, was a luxury his wife

finally decided to tolerate no longer. But once again the Lanza luck held

firm, for Metropolitan Opera baritone Robert Weede moved to a suburban farm

and gave Mario his midtown apartment rent free for two years. Mario replaced

Jan Peerce for the Summer on the Celanese radio hour and managed to do the

occasional concert. But he constantly forced his voice, singing with

dangerous abandon and little finesse. Prolonged abuse of his vocal cords

could easily have ruined his chances for a career. But Sam Weiler

put a stop to that. If Weiler had

been an angelic jinni, he could hardly have timed his entry on the scene more

perfectly. Lanza and Weiler met by accident one afternoon in the Carnegie

Hall studio of voice coach Polly Albertson. Weiler, 31 and already a highly

successful real estate operator, studied with Miss Albertson purely to

satisfy his personal whim and love for music. Lanza visited her regularly to

polish up selections scheduled for the following week's Celanese broadcast. Weiler was

passionately in love with music and knew intimately many of the great singles

of the day. He listened to Mario and quickly sensed the young man's

possibilities but lack of training. "His

concert managers were leading him like a lamb to slaughter," says the

dapper Weiler. "They were obviously interested in making a fast dollar

rather than a long-term investment. Mario was moving in company much too fast

for so untutored an artist. He was utterly at the mercy of conductors and

directors. You might compare him to a sand-lot ball player suddenly scooped

up by the Yankees with no opportunity to learn the fine points of the game

before making his bow in big league ball." Weiler and

Lanza became close friends and eventually Sam signed on as the lad's sponsor.

In return for a 10 percent cut of Lanza's future earnings. Weiler put the

singer and his wife on a weekly allowance of $90 to defray costs of food and

clothing. He cancelled all existing contracts for radio and concert work,

paid off 11 thousand dollars in debts owed by Mario, and financed a schedule

of lessons with Enrico Rosati, who had once coached Beniamino Gigli. For 15 months

Weiler footed all the bills. Top caliber singing stars frequently study 10 to

12 years before venturing an important solo concert, but Lanza was not

entirely uninitiated and could not fully subdue his impatience. Early in 1947

Weiler let him again try his pipes in public. This phase of

Lanza's career was launched at Toronto's Massey Hall. The nervousness which

plagued him in earlier years was gone and a capacity audience welcomed him

warmly. A few days later he sang to a throng of 53 thousand in Chicago's

Grant Park. Then came Hollywood Bowl and a standing ovation from a

celebrity-laden crowd which included Ida Koverman, confidential secretary to

MGM's Louis B. Mayer. Mrs. Koverman arranged a studio audition at which Lanza

played some home-made recordings and then sang an aria from La Boheme

and Victor Herbert's Thine Alone. A day later his signature was on a

movie contract. Before going into his initial picture, That Midnight

Kiss, Mario appeared as guest artist with the Philadelphia and Boston

orchestras and did a two-day debut-stint in Madame Butterfly with

the New Orleans Opera Association. Although he has memorized seven roles, he

has yet to make his second appearance in grand opera. Lanza's MGM

agreement supposedly calls for seven pictures at 25 thousand dollars for his

first, 50 thousand dollars for the second and 100 thousand dollars for the

third. But so immediate was his success on the screen that a grateful studio

gave him a sizeable bonus after his initial film, doubled this after the

second and re-doubled it following the tremendous reception accorded The Great

Caruso. Yet another potential hit, Because You're Mine, is

awaiting release, while in May, Lanza attended for wardrobe fittings for his

latest film, The Student Prince. In 1951 the singer grossed one

million two hundred thousand dollars, of which Weiler took 120 thousand

dollars as his 10 per cent cut. Another 10 per cent went to Lanza's agents,

Music Corporation Of America and Columbia Concerts, Inc. A breakdown of

this 1951 income makes startling reading. He earned 200 thousand dollars on a

concert tour, took 150 thousand dollars (including bonus) from MGM for The

Great Caruso, and chalked up a staggering 500 thousand dollars in

royalties on sales of his recordings. Be My Love has sold almost two

million discs and The Loveliest Night of the Year is close to the

one million mark in sales. Lanza earns eight to 10 cents royalty per record;

a rake-off made even more remarkable by the fact that Dinah Shore and Bing

Crosby collect only half that amount. In addition, Mario received 250

thousand dollars last year from Coca-Cola for his weekly radio shows which

frequently co-star Canadian singer Gisele Mackenzie. The MGM contract, with

two films yet remaining, forbids him stepping into television. While

professional expenses, including agency commissions, leave Lanza with only

eight cents of each dollar he earns after taxes are paid, his association

with Weiler assures him of business-like management and expert investment

guidance. His dollars do not lie idle. With Weiler, he is partnered in tungsten mining and milling at

Austen, Nevada. He also has a small

interest in a nationally-distributed fruit juice drink, although he keeps

this quiet in order not to disturb his radio sponsors, Coca-Cola.His two trotting horses are stabled at

Santa Anita and race in the sulky stakes at Southern California tracks. Lanza’s

interest in racing dates back to early childhood when he clipped every

photograph or advertisement within reach and pasted his paper horses into

scrap-books. In spite of the

fact that motion pictures are only his fourth largest income source, he

confesses the screen is the most important single factor in his success. Nothing establishes an audience so readily

and effectively as a film. The

Great Caruso cost one million two hundred thousand dollars to shoot and

MGM anticipates it will eventually earn 15 million dollars from foreign and

domestic markets. This is probably

over-optimism, but it’s no wonder company executives treat Mario with kid

gloves. Though movies

made Mario, the world’s most debated-over singer displays no feeling of

obligation. He is a master at sulking

and plays hookey at the slightest provocation, regardless of the fact that

such temperament plays havoc with production costs. At a radio rehearsal, his

rich choice of vocabulary once pushed a lady harpist to tears. And he is reliably reported to have so

infuriated songstress Kathryn Grayson that she displayed her displeasure by

sinking her teeth into his lower lip during a love scene for Toast of New

Orleans. Katie, since,

has said she doesn’t care if she never works with him again.“Mario and I

aren’t having a feud,” the dainty, ski-nosed glamour star insists. “I just

can’t stand the man, that’s all.” But Miss

Mackenzie, still a neophyte in the cinema city, comes to Lanza’s defense. “He has great

talent, so naturally he’s bound to have the ego that goes with it,” explains

the Winnipeg brunette, “I was warned. I wouldn’t like working with Mr. Lanza.

He is certainly no sissy. But I’ve met other stars who aren’t half so

considerate.” Certainly,

Lanza could stand an improvement in his public relations.He is as elusive as Garbo, though shyness

seems no part of his nature. He has

MGM publicity men hog-tied. He shows up for interviews if and when he

pleases. Indeed, he seldom deigns to see the press. His personal publicist

alibis that Mario hates talking about himself. The National

Broadcasting Company releases his radio show but most NBC executives have

never met him. The chief of network press relations haven’t even been able to

reach Lanza by telephone although the program is now in its second

season. Lanza records his numbers on a sound stage at republic Film Studios in San Fernando Valley and the

completely edited tape is delivered to NBC in time for broadcast. Apparently Lanza doesn’t stick around to

meet other members of the cast. Songstress Kay Armen, his co-star on a recent airing, has never seen

him. She was asked to record her

numbers several hours before he was due to show up to do his solo offerings. Lanza

apparently cares little what his co-workers and the press think about him. “As

long as my public likes me it doesn’t matter what those reporters write,” he

says. “I asked for trouble when I got into this business. I can take anything

they dish out.”  Table duet by new star

Lanza and veteran Durante finds Mrs. Lanza willing audience.

Meals are Lanza’s

worst problem; he keeps to a rigid diet during filming to curb his leaping

weight.Apparently, he

has a human side. Among his fans last season was Rafael Fasano of Newark, New

Jersey. Miss Fasano was believed doomed to death from Hodgkins Disease. Mario

answered her letters personally and telephones her once a week. Last

Christmas, he called to sing Silent Night to her alone. When she

showed improvement he brought her to Hollywood with her mother and put them

up at his home for several weeks. Even MGM knew nothing of this until a

Newark newspaper reporter got wind of the story and broke it via the

Associated Press.Again, when

rumors circulated Hollywood that aging Louis B. Mayer, co-founder and top man

of MGM, was on his way out, Mario – remembering that the decision to make The

Great Caruso had been Mayer’s – telephoned the MGM head offering his

support if it was needed. Despite this impulsive championing, Mayer was later

replaced by new chief Dore Schary. The Lanzas live

well and enjoy it. He recently purchased a small home for his parents not far

from his own rented, Spanish-style house. Mario’s home has three bedrooms, a

two-story tall living room, a dining room, a rumpus room and a den. The

latter is sometimes used as a fourth bedroom. His elder daughter, Coleen, so

named because of her mother’s Irish ancestry, is just three. Elissa is a

year-and-a-half. Mario says he wants six children, hopes the next one will be

a boy. Mario lives his

career. While he shaves, a record-player spins discs by Caruso or Gigli. He

frequently stays up until dawn listening to operas on wax. His energy is

tremendous, and, despite his hatred of hard work, he keeps his five-foot-10

inches and 50-inch chest in trim by daily working with his personal trainer,

a physical culturist named Terry Robinson. Terry works as his stand-in during

production and looks upon Lanza as a minor god. “This kid got

everything when he was born,” says the awed Robinson, “Looks, charm, voice

and a heart as big as his chest. He’s the great genius of our era. He wrote

50 per cent of the script of Caruso (Note: This will be news to MGM.

The studio paid Sonya Levine and William Ludwig to write the screen-play based

on Dorothy Caruso’s book.) “Mario sings every word the way the composer meant

it, even with popular songs. If the word is chills, he gets chills.” Robinson

regards himself as a high priest of health and even something of a healer. He

built a gym in Lanza’s back yard and gives the tenor a massage at bedtime

after a daily exercise program which varies, between horseback riding, boxing

or weight-lifting. Weight has

always been a problem for Lanza, and, since entering show business, a weapon

too. Although he can keep to a trim 185 with a touch of self-discipline, he

can, with frightening nonchalance, shake MGM executives by rapidly shoving on

excess poundage, anytime officials indicate a course of action which differs

from his own preferences. He merely goes on a high-fat-content diet and

assimilates 15 or 20 pounds with the greatest of ease. It’s more than

coincidence that his avoirdupois jumps whenever he disapproves of a script. Some months ago

MGM called him in to make Because You’re Mine. Lanza looked at the

script and rebelled. When the studio insisted on little or no re-writing,

Lanza merely put on a fast 65 pounds. At 240 he was unphotographable. The

studio took the hint and revamped the scenario. Then Mario hied himself up to

Ginger Rogers’ Oregon ranch along the Rogue River and sweated off the excess

weight by chopping trees, hiking and running. “Weight is

really no problem once you make up your mind to get rid of it.” He insists. “I

take a thyroid prescription, drink a gallon of coffee a day – black – and exist

on one meal, dinner. I skip breakfast and lunch.” Lanza started The

Great Caruso at 185, ended the film tipping the scales at 216. This he

attributes to his desire for authenticity, claiming Caruso grew heavier as he

grew older. However, Lanza fails to state that MGM didn’t shoot the picture

in chronological order and the makeup and photographic departments were hard

put to standardize his appearance on film. When he’s not

dieting Lanza is apt to put away a half-dozen eggs for breakfast. Lunch and

dinner may consist of platters loaded with steak and chicken, heavy helpings

of Mother Cocozza’s spaghetti, and several bottles of beer. He once ate $200

worth of caviar at a single sitting. He still gets breakfast in bed – and his

wife serves it on the maid’s day out. Lanza is not

devoid of idiosyncrasies. He takes vitamin pills by the spoonful, never wears

a hat, chooses neckties of flamboyant color and pattern. He has a canary and

a parakeet, used to be a chain smoker – three packs a day – but he dropped

the habit almost entirely when his voice suffered a prolonged hoarseness. Lanza’s contract

with MGM guarantees him six free months a year for concert or operatic

engagements. Thanks to his movies, he is probably the most potent concert

hall draw in the hemisphere. Last year in Pittsburgh the Metropolitan’s Helen

Traubel sang to a relatively sparse audience. Lanza’s appearance in the

auditorium was a complete sell-out in two hours, and another two thousand

seats were purchased by people anxious to watch him rehearse. Mario is now

considering an offer of 250 thousand dollars for a limited tour of Latin

America. He can pick up 15 thousand dollars a concert on a 12-city Caribbean

itinerary. Rio de Janeiro wants him in November for a three-night stand at 50

thousand dollars. And Australia will guarantee him 15 thousand dollars apiece

for all the concerts he is willing to schedule down under. Nevertheless,

Lanza’s unannounced goal is definitely the Metropolitan. Only there can he

fully build the prestige so necessary to the satisfaction of his ego. And it’s

a safe bet he’d pack the house every performance. “But just

think,” he once wailed to a friend, “all they pay you at the Met is a

stinking thousand dollars a night. A man can hardly afford to sing for

that!” The End

|