The Mario Lanza Story

Photoplay, September 1951

Photoplay, September 1951

Now another voice sings for them and, times being what they are, sings for more millions than the great Enrico ever dreamed of. As Caruso, the name of Mario Lanza works magic, packs the half-empty theatres of an ailing industry, sends box-office records toppling to bite the dust. Here and abroad he's taken the public by storm in such a triumph as leaves Hollywood stripped of adjectives, pop-eyed and gasping.

At this writing his Caruso album heads the best-sellers. Along with "Be My Love" and "The Loveliest Night of the Year," his "Vesti la Giubba" ranks among the top ten. Opera was a word to scare short-hairs with, till this laughing-eyed young man produced a miracle. Singing the incomparable melodies as they were meant to be sung, he's brought mass audiences shouting to their feet and landed opera on the hit parade.

He's broken all patterns and shattered all precedents. But we're going to leave statistics to others and tell the story as we heard it from the four people who know it best. One is a quiet gracious lady with Mario's liquid eyes, who looks as though she might be his older sister. One is a man who came out of the Argonne totally disabled, but kept his humor and his love of life. One is a girl, her spirit as sunny as her face, whose brother was Mario's best friend in the service. The fourth is Lanza himself.

It's the kind of thing that can't happen but does - a wonder tale both simple and fabulous, and steeped in the warmth of those who lived it. So, without more preamble, here is the story of Mario -

As His Parents Began It

Sixteen-year-old Maria Lanza married Antonio Cocozza, recently home from the wars. They named their only child Alfredo Arnaldo, and Maria thanked heaven that he wasn't a girl. Antonio had been gassed at Verdun, his spine bayoneted, his right arm mangled by dumdums. "If it's a girl, call her Verdun," his mother pleaded, and the young people promised. She died a month before the baby was born, which made the promise sacred. Maria drew a breath of relief when they said, "It's a boy."

Alfredo, of course, didn't stick in south Philadelphia. "Is Al in?" his friends would inquire, to Mom's bewilderment. "Who do you mean, Al? There is no Al here." To his family, he became Fred or Freddy. "It doesn't sing like Alfredo," Pop agrees. "Still, it's a nice American name. Al? Al is nothing."

Because of his war injuries, Pop couldn't do much work and his pension wasn't enough. Therefore Mom took over - first as a seamstress, then as a corsetiere. What they lacked in money, they made up in love, and Freddy was the sun of their existence.

"But not spoiled," says Mom. "If I told him no, he might be a little hurt but he knew I meant it."

"Not spoiled," echoes Pop, "but to us he was everything. My wife worked for him. He liked weightlifting, so she made a little gym in his room. This room is over the kitchen. Downstairs she cooks and the ceiling shakes and she runs for her life. Me? I look at this boy and I melt like butter. On Saturday I fix for his breakfast two pounds of steak with six eggs on top. 'Don't tell your mother.' I say. He laughs and eats."

A natural athlete, he shone in sports. Lessons were something else again. "Fred, how will you get your marks? You don't do much homework."

"I'll get them, Mom. You'll see." He got them by intensive cramming before exams. They weren't "A's," but they served.

Till he was nine, they lived with Mom's folks. Grandpop, in the wholesale grocery and trucking business, was something of an old-world autocrat. When he spoke, his children jumped. Freddy didn't jump. Freddy handed Grandpop arguments - respectful, reasonable, but still arguments. This was a new experience to Grandpop. "Maria, this boy."

"Papa," said his daughter firmly, "you brought me up as you wished. I bring this boy up as I wish - to be my friend and not to be afraid."

Autocrat or no, the gaiety and gusto of his forebears ran through Grandpop's veins, and his home was the heart of the family. Every Sunday and holiday they'd gather at Grandpop's to make merry. Freddy spent his vacation at Grandpop's place in Wildwood. Mom and Pop and the other grownups would come out for weekends. Eighteen or twenty, it made no difference. "Grandmom smiled so happy," says Pop, "because she had so many to cook for."

Save in one respect, Freddy's was an average childhood. Before he turned six, it grew clear that his father's consuming passion for opera was reborn in the son. Pop ate, drank and breathed opera. He'd heard Caruso four times. Returning from war, he invested in a Victrola and bought Victor Red Seal records as he could afford them. These were necessities like air and water. Since all the great ones of opera sang for Victor, Pop revered the name. Passing a record shop, he'd stop and smile at the little white dog, ear cocked to His Master's Voice. Pop loved the dog. He stood for all that was best in singing.

Music was in Mom's blood too. She played the piano and sang around the house. Many of their friends were professional musicians. They'd have spaghetti parties, which invariably wound up with singing and records. Wide-eyed, the child would listen till bedtime. It was good that he listened. But he was a baby yet, too young for understanding.

One day, the five-year-old said: "I want to play records."

A wonderful chill struck through Pop's bones. "You want to play records? Instead to go outside and play?"

"Show me how Pop."

Murmuring an Italian blessing, Pop showed him how. "You must wind this handle. It is hard."

"I can do it, Pop."

That was the beginning. Then came the night when they returned from the opera. "He played it twenty-seven times," Grandmom announced.

"Played what?"

"Caruso's Vesti la Giubba." I said, I will count to see how many times he can do it without getting tired. I counted twenty-seven---"

They went up to kiss him goodnight. "Maria," whispered Pop, jubilant. "I should kiss him twenty-seven times."

She smiled softly, "Come. Let him sleep."

As The Boy Lived It

All he knew was that the music excited him. It gave him pelladocca - the Italian word for goosebumps. He wanted no one around when he played the records. Alone, he could drink in every tone and inflection, and lose himself in the radiant maze of sound.

Pop showed him the little white dog and explained what he meant. Caruso and Titta Ruffo sang for the dog. If you were in opera and couldn't sing for the dog - well, that was too bad. Pop shook his head and Freddy followed suit.

Growing older, he pelted people with questions. They began calling him the pint-sized authority on grand opera. Rapt, he listened to Pop describing Caruso. "How does it feel to see an opera, Pop?"

"It feels beautiful, Freddy. You get all dressed up and you take your place and the orchestra leader comes out and everybody keeps quiet and the music begins and the curtain goes up and - you think you're in an opera house, Freddy? No, you're in heaven." Freddy entered heaven at twelve, when they took him to hear "Aida."

His voice? Nobody, including Freddy, knew he had one. Mom hoped he might be a doctor, but the sight of blood sickened him. Well, a lawyer, then. See how he could get the best of an argument, even with Grandpop. They'd send him to college and let him be a lawyer.

At sixteen he said no to Blackstone. "I hate school, Mom, and all the regimentation. I'll finish high school, but forget about college. Give me a little time to feed my way. I know what I want. Show business. I'll find a place."

Now and then at school he'd knock off a couple of high notes that made the guys whistle. Now and then at home he'd sing along with a record - but just for the fun of it and only if Pop was out. To sing in front of Pop, who'd heard Caruso and Ruffo, would have embarrassed him. But Pop came back one day for something he'd forgotten, and the flood of sound from upstairs lifted the hair off his head. For a week he left the house at his usual hour, sneaked round the alley and in through the back door. A week was all he could take without apoplexy. Head whirling, he mounted to his son's room.

Fred saw him standing there, misty-eyed, transfigured. "My boy, you have a truly magnificent voice. God has been good to you."

"Oh, Pop, that's just bellowing."

"It's the nicest bellowing I ever heard in my life. You want to be in show business? Be in show business. Sing."

"One loud note doesn't make a singer, Pop. You have to be good enough for the little white dog. I'm not good enough."

"Let us find out."

"Let's skip it, Pop. Remember what your friend said? 'Never let a boy of sixteen sing. A girl, yes. But the male voice isn't mature enough to work on.' Let's skip the whole thing."

Between tears and laughter, Pop's voice came out shaky. "I am too old for skipping, Freddy. But if you say we wait, we wait."

They waited, and he finished high school. He played records. He gave vent to occasional bursts of song that he couldn't suppress. Mom and Pop exchanged beatific glances but said nothing to Freddy. A voice musn't be pushed.

Nearing nineteen, he came to them, still dubious. "I don't know. Maybe I have a voice. Maybe Pop should take me somewhere for an opinion."

They went to a coach who in her day had sung with the best. For an hour and twenty minutes, Pop sat in the waiting room, kneading his hat, never budging his eyes from the door. Inside, Freddy sang and thought he was singing lousy. Why did she keep him so long? At length she stood up. "You have a phenomenal voice. Let's go talk to your father."

His father rose from the sofa. "Mr. Cocozza, there's something great here. I've never heard anyone so young with such material. But the voice isn't placed yet. Wait a few years."

Pop's mouth opened, but no sound came out. He tried again. The third time he made it. "Excuse me," he apologized through trembling lips. "I touch the ceiling."

That night they held a family conclave. "Mom, you know what it means. You've both made such sacrifices for me. You work so hard. I'll have to study and study." He sprang up, restless. "Maybe I could work on the side."

"No, Fred. You can't do a good thing by doing two things at once. Listen, my son. Only through the hand of God do such things happen. He gives you the hand. Take it. Sing, and fulfill His gift. If I work for you and your voice, I work for Him." Freddy's arms went around her. "Some day I'll make it up to you."

"There is nothing to make up. Come, I will cook spaghetti. This is a happy night, and everyone cries. It is time to laugh."

To give him solfeggio roughly, scale practice - they found an old Italian. "So old," chuckles Pop, "he can't walk up-stairs. I pour him a drink of whiskey, a cup of coffee, and push him up." Voice teachers were thumbed down by the boy himself, who knew that the wrong one could do him more harm than good. But he vocalized with a coach. Most important, he learned pure Italian from his friend, Mario Pellizzon. At home they spoke the dialects of Abruzzi, his mother's birthplace, and Folignano, which his father had left at eleven. Fred needed the McCoy. Pellizzon taught him Roman Italian to such purpose that those to whom it's native swear you're a liar when you say he was born in America.

Also Pop brought home a record, removing it with tenderness from its sheath. "You make me one promise, Freddy. Some time, some place you will sing this for me."

Freddy looked and grinned It was Caruso's "O Tu Che Inseno Al Gli Angli - O, You Who Teach the Angels" - from "La Forza del Destino" "That's quite a promise, Pop. Let's put it this way. If I can, I will."

"Let me live and wait." Prayed Pop.

Spring of '42. The musical grapevine brought the name of Alfredo Cocozza to the ears of William K. Huff, director of Philadelphia Forum Concerts. Huff appeared at the coach's studio to hear him sing. Because the man was not only an expert but wholly impersonal, his words gave Freddy the feeling for the first time that perhaps he'd really found his way.

"Cut or uncut," said Huff, "a diamond's rough. Work, and one day you'll sing for me at the Academy. Only bear this in mind. You've got to sing, sing, sing, and live in a world of music. Cut out everything else. Don't let yourself be derailed."

Then Grandpop stepped in, the unwitting instrument of destiny. He'd been trying to step in for months, but Mom and Pop had stood up to him like a wall. Now, he put the heat on, storming, "What is this? Instead of working, the boy listens to records. Enough is enough. It is time he goes out and does something."

Fred sympathized with his view. "Mom, Pop, I'll drive one of his trucks for a while and make him happy. It won't interfere with the singing, I promise you." Reluctantly they agreed.

Which is how it happened that three young huskies, including our hero, delivered a piano at the academy of Music where Koussevitzky was conducting that night. Crossing the stage, Huff spotted his uncut diamond, dressed like a truck driver, doing a truck driver's work, chewing tobacco like a truck driver. (Now he doesn't even smoke, but at twenty he had to be tough like the rest of the crew.) "What the devil are you doing here?" Huff demanded. Fred told him, and departed about his business.

It was a Wednesday. In Philadelphia the stores stayed open Wednesday night. To lure the trade in, Wanamaker's offered a concert with the world's largest organ and some well-known soloist. Its brilliant windows hove into sight of the boys, still making deliveries. "The heck with work," said Grandpop's young hopeful, "Let's park the truck and dig this concert for a while."

Meantime Huff sat in his box at the Academy, with Fred's coach as his guest and Fred's plight on his mind. As the house lights dimmed, a plan struck and took fire. He leaned toward the coach. Five minutes later she was phoning Freddy's house. No Freddy. Where could she find him? Anywhere. Still working maybe, maybe at Grandpop's or a friend's. She called them all. No Freddy. On a last wild throw she raced down to Wanamaker's.

Eight galleries rise from the rotunda where the concerts were held. Frantically she shoved her way through seven, and on the eighth found Freddy. Just in time to haul the truck back, gallop home and wash, scramble into a suit, grab a couple of sheets of music. As the final note of the final number quivered on the air, they panted into Huff's box.

He took them backstage to the dressing room opposite Koussevitzky's. Drenched as always after a concert. "Sing," said Mr. Huff. A dazed and shaken Freddy broke into opening strains of "Vesti la Giubba," the one aria he knew well. Across the hall, the door stood slightly ajar. Slowly it opened wider to reveal a tall spare figure in trousers and undershirt, towel draped around his neck. The eyes of the two men locked and held. Slowly the elder moved forward, and Freddy's voice soared as if to meet him - soared, sobbed and died in Canio's lament. A moment's silence, broken only by the crazy pounding of his heart. Then he felt himself being embraced, kissed soundly on either cheek - and heard again the unbelievable words. "You have a truly great voice. You will come and sing for me in the Berkshires."

Candor being one of his charms, Mario tells you today that he didn't even know who Koussevitzky was. A big conductor, yes, since he had a big symphony. Otherwise, the name stirred only vague echoes, and he'd never heard of the Berkshire Music festival. If it wasn't opera, Freddy didn't know it. He knew enough, however, to say, "I will come."

He went as Mario Lanza, Cocozza being no handle for a tenor. It was Mom who suggested the masculine variant of her maiden name. Koussevitzky pronounced it perfect, and only on his father's account did Freddy feel troubled. "You're sure you don't mind too much, Pop?"

"Sing," said Pop bravely. "What difference is the name?"

Five weeks of intensive training at Tanglewood in the Berkshires. The sixth week, and an erstwhile truck driver stepped out on his first stage and sang to his first audience, packed with connoisseurs and plain music-lovers. The applause thundered, the New York critics raved, the managers swarmed. He signed with William Judd of Columbia Concerts, and from Philadelphia Mom phoned. "Fred, there's a funny letter for you here. It says, 'Greetings.'"

On a mistaken shipment, they sent Private Cocozza of the Air Force to a spot in Texas whose principal output was dust. A fair share of this lodged in Mario's throat turning his tenor to a gravelly bass. By the time Sergeant Peter Lind Hayes of Special Services came through, hunting material for "On the Beam." Mario was off it. They couldn't hear him for dust. Lying sleepless in his bunk, he watched a shaft of moonlight point like a persistent finger at his locker-box, and the wild idea came to him. Out of the box he took a Caruso record. Over the label he pasted another: Mario Lanza and the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Tanglewood. Tomorrow he'd send it to Special Services. After all, the worst they could do was kill him. Two days later, under general's orders, he joined "On the Beam."

Now that he's a sensation, gleeful scribes pounce on this incident and twist its spirit to prove that the Lanza head was swollen from 'way back. Cheerfully Mario continues to tell it as it happened, let the chips fall where they may. "I yielded to the temptation to get out of hell. I got out of hell. So it couldn't have been a great sin."

A year of touring with the show - singing. A big night at LasVegas for Army Emergency Relief, where they dubbed him the Caruso of the Air Force. At Visalia, Moss Hart heard him and asked for his transfer to "Winged Victory," to lead the chorus of 300. He and Bert Hicks, who played one of the smaller parts, became close friends. Originally from Chicago, Bert had settled in California. He showed Mario Family snaps.

"Hey, who's that?" Perched on the fender of a car, shapely legs crossed, the girl smiled out at him, friendliness in the dark eyes, generosity in the warm curves of the mouth.

"My sister Betty. Went out to stay with my wife and kid in Los Angeles. Landed herself a swell job at Douglas. Great gal."

"Married? Engaged?"

"Uh-uh-"

"Tell her," said Mario dreamily, "to send more snapshots."

Be My Love

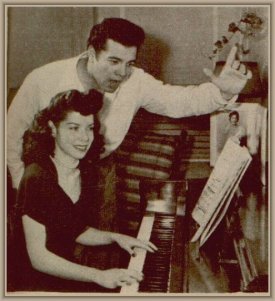

"Winged Victory" hit Los Angeles in June of '44. Bert took Mario home to dinner. In red slacks and an off-the-shoulder blouse, the girl of the snapshots sat across the table from him. Her mother was there too, visiting from Chicago. "Mom," said Mario, already one of the family, "make her stop looking at me."

At twenty-two, Betty had never been in love. Boys came and went whether they went or came didn't really matter. Then a boy walked in, and suddenly the air was electric. His great black eyes laughed at her even when he wasn't laughing. "Make her stop looking at me," he said, and the way he said it turned her knees to water. Within two hours Betty was sunk.

There's an eating place in Hollywood called Romeos Chianti Restaurant, beloved by many for its food and genial atmosphere. To none is it dearer than to Betty and Mario. The owner is an opera lover who plays his rare records for the pleasure of customers. But he changes them himself. Only two others have been allowed to touch them - Danny Kaye, a frustrated opera singer, and Mario.

At the Chianti, Mario gave a birthday party for Bert Hicks, about to be shipped overseas. Then they all climbed into Romeo's big Cadillac, and went to hear "Faust." "Now," Romeo announced, "we go back to the place."

"But it's closed. "

"We will open it."

For the friend of his friend Mario, he'd had a big birthday cake baked, and the champagne Betty ever tasted. On the record machine, the host placed Caruso's "Vesti la Giubba," and Mario sang along with the record. Betty sat rooted, skin prickling with bumps on bumps. They'd told her about his voice, but until you heard it, how could you possibly believe it! Now they were crowding around him, kissing him with true Italian fervor. With true Irish fervor, heightened by music, love and champagne, Betty flung her arms around him and kissed him too. He held her tighter than he did the rest.

On August 29th they went to dinner at Romeo's, just the two of them. The candles burned, the music played in the background. Across the checkered cloth Mario was looking at her as he'd looked that first night, but with a deeper gravity. "I love you, Betty."

"I love you too, Mario."

"Will you marry me?"

She slipped her hand into his where it lay on the table. "You know I will."

He filled their wine glasses. Each took a sip of his own, then of the other's. "Now you're my fiancée." said Mario.

They planned not to tell anyone for a while, and to have a church wedding when the war was over. One thing and another happened to alter their plans.

Several Hollywood people had heard Mario sing, Sinatra among them. Frankie went mildly insane. He picked up a phone and called Columbia Records. "Look, I've just heard a voice like you'll never hear again. Send a contract over. Nail this guy before somebody hooks him."

If he'd asked for the moon in those days, Columbia would have dispatched a jet pilot to fetch it. They sent over a regulation contract. Grateful though he was, Mario refused to sign. "But why not?" pleaded his puzzled friend.

A faraway smile touched Mario's lips. "On account of a little white dog," he said.

The little white dog turned up at a party. As a rule, Mario didn't go for parties, preferring quiet evenings with Betty. As a rule, he didn't sing at parties. Until after their marriage, Betty heard him sing only once. But this party was different. "It's at Irene Mannings," Mario Silva said. "There'll be lots of Hollywood stars, all music-lovers." Our Mario was still fresh enough out of Philadelphia to be curious about movie stars. He went. When they asked him to sing, he sang and knocked them for a loop. Their tingling excitement infected Mario. High with good wine, good music and good people, he sang and sang. At 4 a.m. Walter Pidgeon phoned Hedda Hopper. "Get over here quick."

"Are you nuts? I'm asleep."

"Then wake up. We've got a he-angel singing."

The house was high in the canyon. As she mounted the steps, a cascade of golden sound poured out. "Caruso!" she thought, her gorge rising. "If they dragged me out to hear records, I'll pulverize them." But the boy beside the piano was no record. "My hair stood up," she said later, "and shot straight through my hat."

At seven, Mario begged off and the man came over. For nine hours, while the others went into transports, the man had sat apart, arms folded, eyes on the singer, never saying a word. He made Mario uncomfortable. "What am I, a lesson book, that he stares and studies?" Now he broke his silence, handing Mario a card. "Can you come to my office at two this afternoon?" The card read: "Art Rush-Western Representative for RCA Victor." In the corner a little white dog cocked an ear to His Master's Voice.

Mario managed to sleep for five hours. Art Rush phoned Jim Murray, head of the company, all set to plane out for New York that morning. "Jim, you've got to stay over. You've got to hear this boy." Murray stayed over. Mario sang, and they signed him to a ten-year contract. For the first time in Victor's history, they paid an artist $3,000 just to sign. Mario floated out. The fairy tale had come true for him and Pop. The little white dog thought he was good enough.

On Friday, April 13th, of the following year another dream came true. Discharged from the service because of a bad ear infection. Mario had been summoned by Victor to New York. He refused to leave without Betty.

"But darling, what about our families? And our church wedding?"

Round and round it went, and came out the same way. "If you don't go, I won't go."

Being in love, she yielded. They got their license. At the jewelry counter of a little department store. Mario paid $6.95 for a wedding ring, which Betty has never allowed him to replace. With her sister-in-law Harriet and Mario's friend, Al Gordon, as attendants, they were married in Judge Griffith's chambers in Beverly Hills.

Betty was to spend a few days in Chicago with her folks, while Mario went on to find living quarters and tell Mom and Pop that they had a daughter. With the first job he had no trouble. The second seemed to present some difficulties. Joining him a week later, outspoken Betty asked an outspoken question. "When do I meet your father and mother?"

"Well - they're coming in Sunday."

"What did they say?"

"I haven't told them yet."

"Oh Mario."

"Look, honey, I could talk for a year about how wonderful you are, but it won't be the same as if you're there. Let's tell them together."

"No. It's not fair to them, Mario. You're their only child. You've been so close. Naturally it's going to be a shock. Here's what we'll do. On Sunday I'll go to a movie or something. Then, if they feel like crying, they can cry without having me around to embarrass them."

"Okay, I'll tell them I married an angel."

"You tell them you married a girl who loves you and wants them to love her."

Whatever he told them, his voice was blithe when she phoned after the movie. "everything's wonderful. Come on up."

The door was open, and so were Pop's arms. Betty flew to them. Mom kissed her and called her "my daughter" in Italian. The memory still has power to mist her eyes. "Such beautiful, gentle people. They took me in, and it was as if I'd belonged to them forever."

On July 15th, with all their loved ones present. Betty and Mario were married by Catholic ritual in the lovely little church of St. Columbo.

Fulfilling the Gift

For a while it was Eden without the serpent. From the Park Central they moved to Robert Weede's apartment. Weede, whom they met at a broadcast, said: "I'm going to live on my farm. You like my place? Take it." His place was perfection - in the heart of the 50's, overlooking Rockefeller Center's ice-skating rink.

Mario worked with a coach. He made test records for Victor. Every night they walked down Fifth Avenue, laughing, planning, window-shopping, stopping at some juice bar for a tall cold drink. They'd go down to Philadelphia, or the folks would come up. Pop would stand at the window, feasting his eyes on the majesty of St. Patrick's. "Freddy, we go light a candle to St. Anthony for all the beautiful things that are happening."

But $3000 slips away fast in New York. Against his judgment, almost against his will, Mario accepted a radio offer of twenty-six weeks on "Great Moments of Music" for the Celanese Company, taking the place of Jan Peerce. From the first it made him miserable - a great opportunity that he felt he wasn't yet up to. By Mario's code, you don't go before the public except at your best. To achieve his best, he needed real voice training now with some fine Italian teacher. Yet where was the money to come from? Already they were floundering in debt and he was sinning against his own musical standards. Before each broadcast he paced and shivered, physically ill. "I can't go through with this torture, Betty. It's all wrong."

"Something'll happen to make it right. You'll see."

Sam Weller happened. Weiler was a wealthy real estate man, in love with singing. Aware that he had no voice, he took lessons anyway just for the hell of it, and his teacher was Mario's coach. One day he arrived ahead of time. Through the open transom, a glorious tenor swelled, and suddenly Weiler didn't want to sing any more. Unable to contain himself, he knocked. "I know I shouldn't intrude, but I had to get a look at you. May I stay and listen?

Ordinarily, Mario would have frowned the suggestion down. But this was such a smiling, kind-faced man that you couldn't say no to him. When Mario left, Weiler stared after him. "Why, with a voice like that, does he look so unhappy?" The coach told him, and Weiler forgot his lesson. "I want to talk to that boy. Where can I reach him?"

"He sometimes hangs out at a health food shop across the way."

Weiler found him. They adjourned to the park Central drugstore. Mario's not one to spill his woes to a stranger. But talking to Sam was like talking to your brother. "Just tell me about yourself. Maybe I can help." Four hours and thirty-five cups of coffee later, they'd reached a verbal agreement. Sam was going to take over. "I want to sing and I can't sing. Through you I can. Just one thing more. I'd like to meet your wife."

"That's easy. Come to dinner."

"Fine. What can I bring her?"

"She's crazy," laughed Mario on top of the world, "about little toy dogs."

They climbed five flights of stairs to where Betty waited on the landing. "Honey, this is Sam Weiler. He's going to be someone very special in our lives."

Gravely Sam handed over a stuffed puppy, done up in cellophane. Betty put an arm around him and kissed his cheek. Not because of the dog nor even because of Mario's special introduction. But because when you looked at him, you liked him. Instinctively she knew that this man could never do anything but good.

Today he's Mario's manager, and the families are like one. Actually his management began when he straightened out their money tangles and gave them so much a week to live on. There was no awkwardness involved. In Betty's words, "It was like your mother and father walking in, saying 'I'm going to take care of you." He settled the Celanese contract after eleven broadcasts, removed Mario from circulation and took him to Enrico Rosati, famous teacher of Gigli.

Rosati's greeting was unconventional. "You," he said, gleaming-eyed, "are a so-and-so because you are destroying what your mother gave you."

Mario tried to duck with a feeble jest. "What about my father? Didn't he have something to do with it?"

"The papa, yes. But the mama, she had the baby. Why do you sing before you are ready to sing?"

The tongue lashed on, dropping Mario's morale lower than an earthworm. Then, as abruptly, it stopped. "Sing!" commanded the ogre. He sang. Deigning no comment, Rosati strode to the door. "Come, listen to something!" he shouted. Like two good mice, his wife and secretary stole in and sat down. Mario sang again. Head bowed, fingers still on the keyboard, the old man spoke as though to himself. "For thirty-four years since Gigli I wait for this voice." Then he looked up. "You will come at eight in the morning. This means not one minute before nor one minute past, but eight precisely."

"Yes, maestro," said Mario meekly enough, but the words were a song.

Fifteen months with Rosati. Then the concerts began. His first Chicago appearance drew 35,000, his second trebled that. On the strength of Claudia Cassidy's review, the St. Louis Symphony booked him in. Though he'd mastered only four operatic roles, Edward Johnson, then manager of the Metropolitan Opera, made him a bid. Opera is the lodestar of Mario's professional life, but he declined. "I have too much respect for the Met to make my mistakes there."

In Hollywood, the Bowl was scheduling its '47 season, looking for a big-name tenor to sing with Eugene Ormandy's orchestra in August. Art Rush took a record to Ida Koverman, who was (1) right hand to Louis B. Mayer (2) an influence in musical circles. "I want you to hear this voice," said Rush. It was an acetate record, which does justice to no voice, but it sufficed. Mario was engaged for the Bowl, and Koverman played the record for L.B. then she showed him a photograph. "You mean," he demanded, "that this voice comes out of this face?" "Wait. Wait till you hear him."

At every concert Betty sits out front, part of the crowd, caught up in the general delirium, forgetting that Mario's her husband, beating her hands like mad with the rest. Once it's over, she may feel a trifle red-faced. What is she, a claque? But while he sings, she's lost. The Bowl concert was no exception. The whole place rose to its feet and let out a roar. In all the Bowl's history, Jascha Heifetz rated the longest standing ovation - sixteen minutes Mario's ran four minutes under.

Koverman threw a big party. Studio calls clogged the phone, but the inside track belonged to M-G-M. work came to a halt while fifty-five assorted executives gathered on a sound stage for the command performance. At its close, the boss pumped the performer's hand. "You're going to be our singing Clark Gable." Mario grinned. Last April they'd offered him a regulation contract, which he'd turned down. Movies were fine, but to be chained to them, no, since his primary purpose in life was to sing. Now they took him on his own terms - six months a year for five years, all record and radio rights reverting to him. An unusual deal, not to be wondered at in an unusual story.

Mario's sentimental. Whenever they go back to New Orleans, he insists on the same suite in the same hotel where they first stopped. New Orleans is the town of his operatic debut in "Madame Butterfly." To Mario, it's also forever "Colleen's town."

The heat was stifling, but the Lanza appetite rises above heat. With Sam and Sam's wife Selma. Mario and Betty went to Arnaud's for dinner. Betty ordered curried chicken, swallowed a forkful and fled. To date, she can't look curried chicken in the face. Selma hurried after her. When anything's wrong with his wife, Mario flops. Not this time however. They'd been waiting for the rabbit test, which hadn't come back yet. Mario's hand smote the table. "Don't tell me!" he crowed "Rabbit or no rabbit, this is it."

At 2 p.m. on December 9th, the baby was born, after twenty-two hours of labor. They finally prevailed on Mario to go home. His tortured face wasn't helping Betty any, and he had to record next day for "That Midnight Kiss." When the call came through, he was singing "Celeste Aida." Betty woke up to find her husband on one side, Sam on the other, both looking as though she'd done something unheard of. "It's Colleen, honey," said Mario. "she's a doll." The name was his choice. People often asked him if his wife was Italian. "No," he'd always answer. "She's my little Irish colleen."

Another shining milestone had been passed earlier. At the end of his first concert tour, Mario had taken his mother's patient hands in his. "Now it's over, Mom. Now you quit working, and I work for you." When Colleen was six months old, her grandparents came out to visit. Mario finished "Toast of New Orleans." Then the whole family descended on Philadelphia for the opening of "That Midnight Kiss."

"This was a week!" sighs Pop. "Cameras shooting us. From the station to the hotel with motorcycle cops.

"Even on the stage they call us. Freddy stands there with Kathryn Grayson and Betty and laughs and makes with the finger. My wife goes out like a queen. Me it scares. 'Smile, Pop,' says Betty. 'Smile or I'm going to tickle you."

The Legion gave a dinner. President Truman was to speak, and Mario to sing. Being there was enough. Having six generals ask Pop about his wounds was almost too much. But the moment that burst their hearts was yet to come.

Truman arrived late, and had to leave early for a scheduled broadcast. "Mario Lanza is waiting to sing for me." He lifted his eyes to the young man on the balcony. "I'm sorry Mario. Another time, I hope." And his hand went to his temple in a smart salute.

"I grab my wife. Do we dream, is it real that the President of the country we love so much stands before all and salutes our son? Mario he calls him - not Mr. Lanza, but Mario. How can such a thing happen?"

"Yet it happened," says Mom, eyes brimming.

While such things were happening, Grandpop fumed. Mario's tight schedule gave him barely time to breathe. But what was a schedule to Salvatore Lanza! "You mean I can't have my own grandson in my own house?"

"Look Grandpop, the last show is out at eleven Saturday. Then we'll come to the house."

Muttering, Grandpop retired to his warehouse and ordered half the stock on its shelves sent home. A feast was prepared such as even the Lanzas had never yet beheld. Many were invited, and more showed up. Outside, the crowds set up a rhythmic roar. "We - want - Mar-io, we - want - Mar-io." Inside, Grandpop filled wineglasses, including his own, "eat, drink and be happy, everybody." He filled the glass again. "Saluta, Freddy."

"Salvado, that's enough," warned Grandmom.

"Why enough? I never died yet." He poured another glass. "Freddy, saluta. Tomorrow I go out and kiss that truck."

"We'll kiss it together, Grandpop." Mario promised.

The papers had every tenor in the country playing Caruso. In her heart Betty always knew that Mario would do it. Edward Johnson had told Jesse Lasky, who owned the story rights, that Lanza was his man. Lasky tried to borrow him, but M-G-M wasn't lending. At length they joined forces. Through the endless complications that followed, Betty's faith never wavered. Not even when M-G-M called the whole thing off.

"Don't worry," she said. "They'll call it on again."

"I don't get it," said Mario. "They've already assigned writers."

"They've un-assigned 'em." said Lasky.

"They're afraid of opera. Opera heads the list of don't. But I'm calling Mayer."

Mayer said: "Give me a few days." Within those few days he rallied his more fainthearted associates and dumped a small Fort Knox into Leo's lap. By such hairs does movie history hang.

Once it was set, Mario's feet turned slightly chilly. "I'm frightened, Betty. It's like putting yourself on a pedestal with your idol." This feeling wore off. His aim is not to be Caruso the second, but Mario Lanza. He never reads reviews. He sings his best and, if the people like him, that suits him fine.

While he was making "Caruso," Grandmom's namesake, Elissa, was born - on December 3rd, two years after her sister. This time Mario was there, holding his daughter a half hour after her birth. Betty heard his laughter mingling with the baby's squall, and decided she was still under. Then his voice came through. "A bass, if I ever heard one! Aren't you ashamed, and your father a tenor!"

CARUSO SINGS TONIGHT. That's how the posters read on Hollywood Boulevard the night of the premiere. But the kids sang too. As Mario helped Mom and Betty out of the car and Pop followed, a fresh young soprano lifted itself in serenade, stilling the clamor. "Be my love, for no one else can end this yearning." Behind the ropes and up through the bleachers, it caught like wildfire. "Just fill my arms the way you've filled my dreams…" Spontaneous, unrehearsed and heartwarming, it dissolved Mom in tears…"Eternally, if you will be my love…"

"You see?" said Mario. "You've made my mother cry."

"With happiness, Fred."

"With happiness, she says. So thank you for all of us. Whatever happens inside, you've started our evening with a bang."

What happened inside no longer needs telling. Except that Mario sat between Betty and Mom, holding a hand of each. And that Pop all but fell out of his seat applauding. After each number he'd lean toward his son. "Go on Freddy, clap, isn't it good? Clap for Caruso." And Mario laughed.

Says he: "I watched Mom and Pop. For me, it was their evening. For me it was most exciting because my mother and father were there."

Says Betty: "We had a few close friends in later, about 125. After they went, we sat like a couple of zombies. There were no words left. We just kissed each other."

Say Mom and Pop: "When God gives so much, it chokes you up, and you don't know how to express yourself to Him. So we just went on our knees and told Him thank you."

As "Be My Love" started climbing, Betty predicted. "It'll hit a million."

Mario said, "Never."

"Bet $150 to $100."

"Be My Love" made it in eight months. In Victor's sixty-five years at the same stand, Lanza's the first Red Seal vocalist to sell a million copies. Iturbi did it with "Polonaise," but it took two years. Official presentation of the gold record will be made by Iturbi. Unofficially, Mannie Sachs flew out with it. Betty stuck a palm under her husband's nose. "Okay pay off."

He signed a traveler's check. "There. It's the nicest bet I ever paid."

"And don't think I won't spend it. How about $200 to $160 that 'Loveliest' does the same?"

"Loveliest Night of the Year?" is well on its way. Caruso snowballs. The Lanza program for Coca Cola has sent TV-ers back to radio. Protests flood the station. "Why only seventeen weeks? Why not forever?" Answer: because of other commitments. A picture called "The Big Cast." A concert tour in the fall.

Everything's wonderful, but for Mario the thrill of thrills lies ahead. His heart belongs to opera. "In movies you play someone else, which I love, but you sing to a mike. In concert, you sing to the people, which I love, but you're Mario Lanza in formal dress. I'm against formal dress. I'd rather sing in a shirt and pair of pants. In opera you're somebody else and you sing to the people. When I stand on the stage of La Scala or the Met, that will be my heaven."

Victor di Sabbata of La Scala has invited him to open the season in Milan. His acceptance depends on conditions still in the making." I can wait, I have time, I'm not thirty yet. Musically," says the guy whose music has electrified millions, "I'm not even born."

At Home

Like any barbershop tenor, Mario sings in the shower. His vibrancy brings a room alive. Talking to you, he makes you feel important. This is no trick, but a genuine warmth for people. His eyes are clear as a child's, and honesty is one of the clues to Lanza. When he sings, it's the original key. If you own a Lanza autograph, it's real. He won't allow his signature to be faked.

Naturally gay and goodhumored, he can explode when the occasion warrants, but gets over it quickly. Sourpusses depress him. In hiring help, Betty looks for cheerfulness first, efficiency second. Next to music and people, Mario loves food. Sitting at one meal, he'll be planning the next. He's forever carting delicacies home, three times more than you need. If at Mario's table a guest had to be told. "That's all there is," he'd crawl off and die.

Sunday's family day, which includes all the Weilers and any close friends who feel like dropping in. Mom and Betty take over the kitchen. Pop and Mario stroll by.

"Make it rich, Mom."

"I've been making it rich for thirty years."

"A little more oil." Suggests Pop.

Till suddenly Mom has enough. "All supervisors out! Clear the kitchen."

They live in Beverly hills, and life centers around the home Mario bought them. Each morning Pop and Colleen have a standing date. She waits at the window. "Buon giorno, Pop-pop." Trailed by Tenor, the spaniel, they go for an airing, wave to Charles Boyer and the mailman, discuss affairs. "Like a little old lady she talks to me, and that's my best fun - to be with Colleen and the little dog Tenor."

Both babies have Mario's eyes, for which Betty thanks Providence. (not that there's anything wrong with her own. ED.) Like his father before him, Mario looks at his kids and melts. Colleen said "mamma" first. Elissa said "dada" first, and the house fell down. Every night there's a ritual. After her bath Colleen appears on the little balcony over the living-room and dangles her hand. Mario picks up a folded paper and hits it. Gurgles of laughter greet this terrific joke. Then they all go upstairs. God is asked to bless a top-heavy list of creatures, ending with Tenor and Pretty-boy, the canary. "Now sing the baby song." Keeping it soft, Mario sings the Virgin Slumber Song, recorded for Colleen.

No matter how late, nor how many people they've had in, the Lanza's take a drive before bedtime, as they used to take walks in New York six years ago. As in New York, they laugh and plan and dream.Mario will doubtless sing all over the world, but California's home. One of their dreams is to buy a ranch out there, where they can raise animals.

Mario's not superstitious. He and Betty were married on Friday, the 13th. It's their lucky number. Around the number Betty designed a money-clip, and inscribed it: "Darling, may we live as long as we love and love as long as we live."

He's not supersticious, but he won't move from here to there without that clip.

Postscript

One night when some friends were gathered, Mario put a platter on the turntable. "This is Pop's record. I made it for him and Mom."

The disc whirled. "O tu che inseno al gli angli," it sang in Mario's voice. At the first word Pop couldn't talk any more. Time faded.

"You make me one promise, Freddy. Some time you will sing this for me."

"That's quite a promise, Pop. Let's put it this way. If I can, I will."

The song reached its end. Still incapable of coherent speech, Pop grabbed his son and kissed him five times, maybe six.

"Someday," he says,"we have a party together, me and my wife, Colleen and little Elissa. I will tell them about a boy five years old who sits in the room and plays a great singer's recod twenty-seven times. Who is the boy? Your Papa, Mario Lanza, a great singer. You know what they're going to say? Let us play papa's record twenty-seven times. So we're going to do that - me and my wife, Colleen and little Elissa." A rich chuckle escapes him. "This will be a party."

"With coffee and cake." Smiles Mom.

And Pop adds the benediction. "Let us live and wait."